10 Pioneering African American Architects and the Legacy Buildings They Designed

The legacies of African American architects and designers—who, throughout the existence of this country, have contributed to the intellectual, aesthetic, cultural, and commercial development of our built environment, although often in the shadows—are far-reaching and varied. As we celebrate Black History Month, Interior Design looks at 10 pioneering men and women, from the accomplished architects of campus buildings at Duke University and the Tuskegee Institute to the designer of mid-century Hollywood homes of the stars. Each were among the first in their field and, thanks to their increasingly recognized accomplishments, far from the last.

Robert Robinson Taylor (1868-1942)

Born in Wilmington, North Carolina in 1868, Robert Robinson Taylor was the first African American student allowed into MIT, graduating in 1892. Moreover, he was the first African American accredited as an architect in the country. Over his long career, Taylor built three colonial-style Carnegie Libraries for black colleges in Alabama, North Carolina, and Texas; a partnership in the 1920s with another black architect, Louis H. Persley, resulted in the Dinkins Memorial Building at Selma University and the Renaissance-revival Colored Masonic Temple in Birmingham, after which he went on to design the famed Booker T. Washington Agricultural & Industrial Institute in Liberia. But Taylor’s most enduring legacy stands at the African American vocational school Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), where he worked as vice president under Booker T. Washington. Throughout the last decade of the 19th century, Taylor designed more than two dozen buildings on its campus, including Ellen Curtis Hall, Sage Hall, White Hall, and Tompkins Hall. The school’s original chapel—which Tuskegee graduate Ralph Ellison described as having “sweeping eaves, long and low as through risen bloody from the earth like the rising moon; vine-covered and earth-colored as through more earth-sprung than man-sprung” in his 1952 novel Invisible Man, was lost to a fire in 1957. Taylor’s achievements on the campus remain a source of inspiration for future generations: Tuskegee’s Robert R. Taylor School of Architecture and Construction Science is named for him.

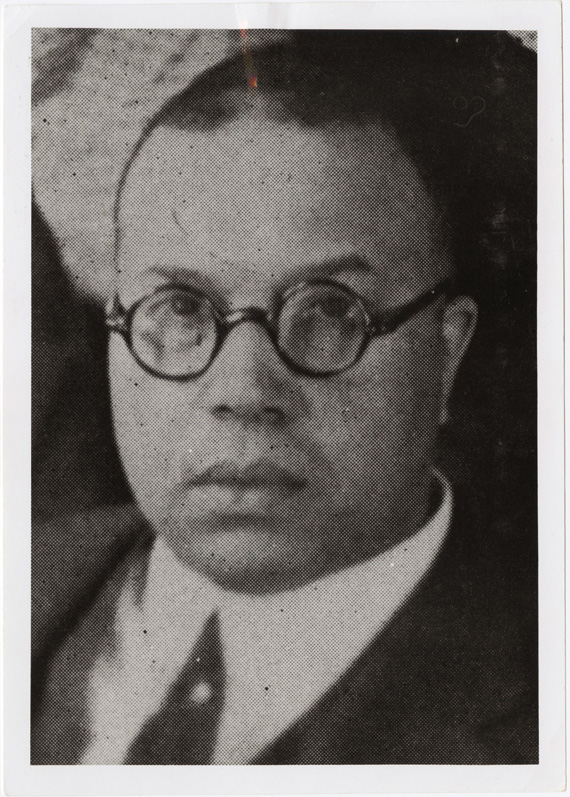

Julian Abele (1881-1950)

Such is the perversity of racism: Until 1961, North Carolina’s Duke University wouldn’t allow African American students to graduate from its English Gothic and Georgian buildings—and yet those very buildings were designed by a black architect. The first African American architecture graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, Julian Abele studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, before joining the eminent Philadelphia firm of Horace Trumbauer, where as chief designer he created Beaux Arts buildings for the Philadelphia Free Library and Museum of Art, Harvard’s Widener Library, and a pile of Gilded Age mansions in Newport and New York City. After Trumbauer’s death in 1938, Abele took over the firm itself, and in 1942 was admitted into the American Institute of Architects. His work for Duke—more than 30 buildings including its chapel, library, stadium, medical school, and hospital—consumed the rest of his professional life until his death in 1950. In recognition, the university in 2016 named the area encompassing those original academic and residential buildings Abele Quad. Julian Abele portrait, courtesy of University of Pennsylvania Archives.

Such is the perversity of racism: Until 1961, North Carolina’s Duke University wouldn’t allow African American students to graduate from its English Gothic and Georgian buildings—and yet those very buildings were designed by a black architect. The first African American architecture graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, Julian Abele studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, before joining the eminent Philadelphia firm of Horace Trumbauer, where as chief designer he created Beaux Arts buildings for the Philadelphia Free Library and Museum of Art, Harvard’s Widener Library, and a pile of Gilded Age mansions in Newport and New York City. After Trumbauer’s death in 1938, Abele took over the firm itself, and in 1942 was admitted into the American Institute of Architects. His work for Duke—more than 30 buildings including its chapel, library, stadium, medical school, and hospital—consumed the rest of his professional life until his death in 1950. In recognition, the university in 2016 named the area encompassing those original academic and residential buildings Abele Quad. Julian Abele portrait, courtesy of University of Pennsylvania Archives.

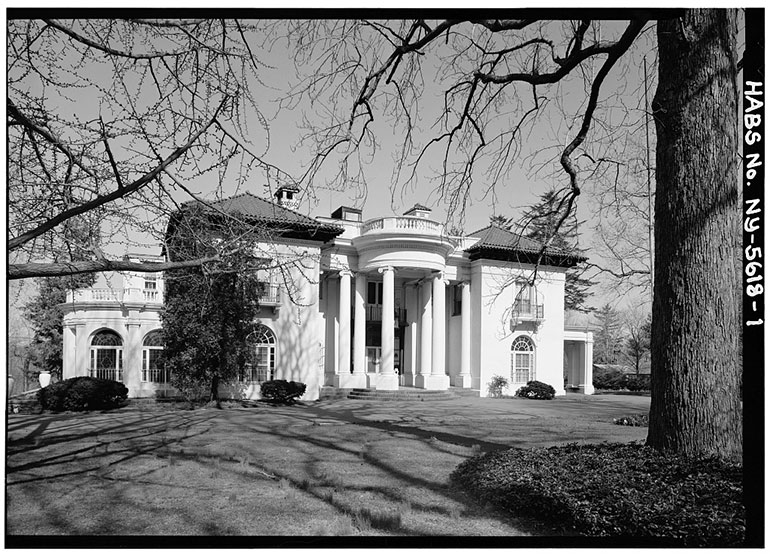

Vertner Woodson Tandy (1885-1949)

One of the African American students studying within the storied halls of Taylor’s Tuskegee Institute was Kentucky-born Vertner Woodson Tandy, who enrolled there in 1904 to study architecture. The next year, he matriculated to Cornell, where he helped establish the first African-American Greek letter fraternity (Alpha Phi Alpha) before graduating in 1908 and moving to New York City. The first black registered architect in New York state, Taylor soon partnered with George Washington Foster, the first black registered architect in New Jersey, and from their office on Broadway the team went on to establish much of 20th-century Harlem and surrounding areas. Villa Lewaro, a 1916 Federal/Regency Revival manor house in Irvington, NY for hair-care magnet Madame C.J. Walker was a triumph; while the 1925 Neo-Gothic-style Mother AME Zion church is the oldest African American church in New York City, and a city landmark. The Abraham Lincoln Houses urban renewal project in 1945 was one of the largest projects of its kind, a collaboration with Skidmore Owings & Merrill and Edwin Forbes, with a budget of $8.5 million. When Tandy died in 1949, his funeral was held at Harlem’s Saint Philip’s Episcopal Church—a fitting tribute, since he and Foster had designed it in 1910. Portrait of Vertner Woodson Tandy, courtesy of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

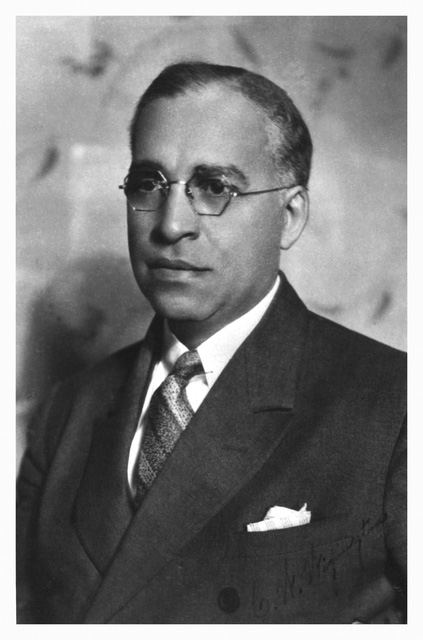

Paul R. Williams (1894-1980)

Paul Revere Williams was born in Los Angeles, but it many ways Los Angeles became itself through him. Williams extensive work designing Hollywood homes defines a certain mid-century glamour: The curving staircase, the pink-and-green palette, the retractable screens, the patio flowing directly from a living space, all came in large part from the desk of Williams. The first African American member of the AIA (in 1923) and its first black fellow (in 1957), Williams built houses for everyone from Frank Sinatra to Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz to Cary Grant, along with the St. Jude Children’s Hospital in Memphis, pro bono, for his pal Danny Thomas. In the end, Williams’ portfolio included thousands of buildings, among them the renovation of the fabulous Polo Lounge at the Beverly Hills Hotel (where he also designed the Paul Williams Suite, named in his honor) and the Georgian Revival-style MCA Building in Beverly Hills. He was also one of the architects who in 1961 designed the futuristic Theme Building at LAX. And his sense of glamour lives on: In 2017, 37 years after his death, the AIA awarded him its Gold Medal, the body’s highest honor. Portrait of Paul Revere Williams by Herald Examiner Collection, courtesy of The American Institute of Architects.

Clarence W. “Cap” Wigington (1883-1967)

Far from La La Land, the first African American registered architect in Minnesota was hard at work whipping up creations all his own. Clarence W. “Cap” Wigington, who didn’t have a degree in architecture but who worked under then-AIA president Thomas R. Kimball after attending an art school in Kansas, settled in St. Paul in 1913 and became famous for the fanciful yet accomplished architectural ice carvings he created for the city’s Winter Carnival. He built in brick and stone, too, of course, as the country’s first African American municipal architect, eventually contributing 60 buildings that embodied the early 20th century “City Beautiful” movement. His Como Park Elementary School from 1916 defines the modern style, but it’s his later triptych—1928’s Highland Park Water Tower, constructed of Kasota and Bedford stone and still in use today; the 1941 WPA Holman Field Administration Building at the St. Paul Downtown Airport; and a stately pavilion on the Mississippi River, completed that same year and re-named for Wigington in 1998—which earned listings on the National Register of Historic Places. Portrait of Clarence W. Wigington, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

Far from La La Land, the first African American registered architect in Minnesota was hard at work whipping up creations all his own. Clarence W. “Cap” Wigington, who didn’t have a degree in architecture but who worked under then-AIA president Thomas R. Kimball after attending an art school in Kansas, settled in St. Paul in 1913 and became famous for the fanciful yet accomplished architectural ice carvings he created for the city’s Winter Carnival. He built in brick and stone, too, of course, as the country’s first African American municipal architect, eventually contributing 60 buildings that embodied the early 20th century “City Beautiful” movement. His Como Park Elementary School from 1916 defines the modern style, but it’s his later triptych—1928’s Highland Park Water Tower, constructed of Kasota and Bedford stone and still in use today; the 1941 WPA Holman Field Administration Building at the St. Paul Downtown Airport; and a stately pavilion on the Mississippi River, completed that same year and re-named for Wigington in 1998—which earned listings on the National Register of Historic Places. Portrait of Clarence W. Wigington, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

Beverly Loraine Greene (1915-1957)

Beverly Loraine Greene (1915-1957)

By the time Chicago-born Greene arrived at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in the early 1930s, the campus was integrated—but just barely. She was the first African American woman to graduate with a Bachelor of Science degree in architectural engineering, in 1936, and the first to earn a master’s in city planning and housing the following year. A coveted assignment working on New York City’s Stuyvesant Town (a complex in which African Americans would not initially be allowed to live) followed, although Green left the project when Columbia University’s masters program in architecture wooed her away with a scholarship. From there, the world was Greene’s build site: with Edward Durell Stone, she completed a theater at the University of Arkansas in 1951 and then collaborated with brutalist master Marcel Breuer on and the arts complex at Sarah Lawrence in 1952 and the UNESCO United Nations headquarters in Paris, which opened in 1958. Sadly, her death in 1957 at age 41 meant the first African American woman registered as an architect in the United States didn’t live to see its completion, nor the buildings she designed for New York University. Portrait of Beverly Loraine Greene, copyright Illini Publishing Company (Illini Media), courtesy of the University of Illinois Archives.

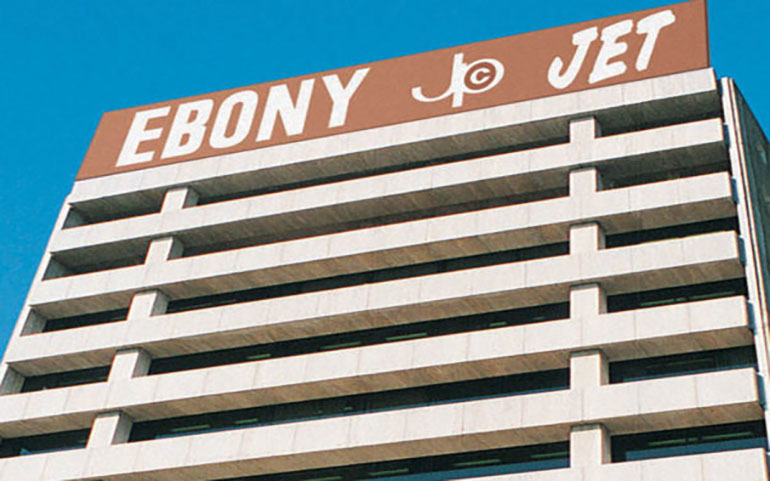

John Warren Moutoussamy (1922-1995)

The Chicago skyline is justly known for buildings by William Le Baron Jenney and Mies van der Rohe, but one of its great Modernist profiles was designed by the entrepreneurial John Warren Moutoussamy. The first African American architect to make partner at a large firm (Dubin, Dubin, Black & Moutoussamy), he was the designer of the Johnson Publishing Company Building, home for five decades to two essential chronicles of black culture, Ebony and Jet magazines. Moutoussamy studied at the Illinois Institute of Technology under van der Rohe himself, whose influence can be seen in the profile of the 11-story building, which Moutoussamy completed in 1971, featuring lively interiors by Arthur Elrod and William Raiser. In 2017, the building, located at 820 South Michigan, earned the official Chicago Landmark Designation; it has been transformed into an apartment building and remains the city’s only downtown tower designed by an African American.

John S. Chase (1925-2012)

In 1950, the Supreme Court successfully challenged the “separate but equal” segregation doctrine, broadening access to educational institutions for African Americans across the country—including for John S. Chase, who was finally able to attend the University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture thanks to the Sweatt v. Painter decision. After graduation, though, no firms would hire him, so Chase founded his own practice. In 1956, he became the first African American architect licensed in Texas and established himself as one of the state’s great modernists with projects that included the 1963 Riverside National Bank and a triptych of projects for Texas Southern University: the 1969 Martin Luther King Humanities Center, 1976’s Ernst S. Sterling Student Center, and the Thurgood Marshall School of Law Building in 1979. Chase established an international presence with a commission for the U.S. Embassy in Tunisia, while closer to home, he oversaw the renovation of the Astrodome. A founding member of what later became the National Organization of Minority Architects, Chase received an AIA Whitney M. Young Citation and an AIA Fellowship in 1977. Three years later, President Jimmy Carter selected him to serve on the U.S. Commission on Fine Arts, the first African American to do so, and Chase was subsequently instrumental in that body’s choice of Maya Lin for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

Norma Merrick Sklarek (1926–2012)

Norma Merrick Sklarek worked with some of the most preeminent architects on some of the most famous buildings of the 21st century, but because she was an African American woman, she was at best billed as project manager on many of the buildings she helped design. Born in Harlem, Sklarek graduated from Columbia’s School of Architecture in 1950 and soon landed a job at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, in 1959 becoming the first African American woman to become a registered architect in New York. A job at Gruen Associates in Los Angeles brought her to California, where in 1962 she was among the very first African American women architects registered in the state. As Gruen’s director of architecture, she oversaw major projects such as the California Mart and collaborations with César Pelli that included the Pacific Design Center and the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo. As vice president of Welton Becket Associates—and the first African American woman named an AIA Fellow—she led construction of Terminal One at LAX in 1984, then left WBA to form Siegel Sklarek Diamond, the largest woman-owned practice in the U.S. Sklarek served as lecturer and mentor to countless architects for the rest of her career, winning the AIA’s Whitney M. Young, Jr. Award in 2008. Howard University furthers her posthumous legacy with its Norma Merrick Sklarek Architectural Scholarship Award. Portrait of Norma Merrick Sklarek, courtesy Gruen Associates.

Wendell J. Campbell (1927–2008)

Wendell J. Campbell (1927–2008)

Raised in East Chicago with a contractor father, Wendell J. Campbell studied on the GI Bill with Mies van der Rohe at the Illinois Institute of Technology, but found no firm willing to hire an African American architect. Instead, he turned to urban planning, working on affordable housing projects for the Purdue-Calumet Development Foundation. In 1966, he took his career into his own hands, founding Wendell Campbell Associates, later to become Campbell and Macsai Architects, and helped to define much of urban Chicago through his work overseeing the extensions and renovations of the McCormick Place Convention Center, the DuSable Museum of African American History, Trinity Church, and the Chicago Military Academy at Bronzeville. Campbell’s enduring achievement, however, is his work co-founding the National Organization of Black Architects in 1971, a crucial hub whose scope later broadened as the National Organization of Minority Architects. In 1976, Campbell received the Whitney M. Young, Jr. Award from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and in 1979 was named an AIA Fellow, and served on the boards of AIA Chicago, the Chicago Architectural Assistance Center, and many other organizations, working nonstop until his retirement in 2006. Portrait of Wendell J. Campbell, courtesy of the American Institute of Architects.