10 Questions With… French 2D

Anda and Jenny French live and work around the same Boston neighborhoods in which they grew up. Together, the sisters poked around the office of their famed architect parents, Linda C. Neshamkin and John W. French, who took them on urban field trips. While both left to complete their studies—Anda for a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture at Barnard and a Master of Architecture from Princeton; Jenny for a Bachelor of Arts in Art History and Studio Art from Dartmouth and Master of Architecture from Harvard University Graduate School of Design—they returned to their hometown and, in 2008, founded their own firm, French 2D.

Perhaps all these familiars inspired their interest in “strange housing types,” or homes that incorporate radical ideas of spacial and interpersonal organizations.

Or perhaps their refusal to separate the practices of fine art, architecture, and sociology simply necessitates new forms. Both have kept one foot in the classroom—Anda is currently a visiting lecturer in the Princeton University School of Architecture, while Jenny is an assistant professor in practice of architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, and the coordinating faculty in architecture for its Discovery Program—and another in the art world, exhibiting at MoMA and the U.S. Pavilion of the 13th Annual Venice Architectural Biennale.

Recently, the sisters sat down for a Zoom with Interior Design to share insights on their latest projects, preservation and authorship in architecture, and the enduring spell of the film “Beetlejuice.” [Editor’s note: this conversation has been edited for clarity.]

Interior Design: When was the first time you remember really noticing the architecture or design of a space?

Jenny French: The Montessori elementary school we went to—the Advent School in Boston—was project-based and the two adjacent townhouses had all kinds of nooks and shag carpets. Even though we weren’t in the same class, it was a way for us to encounter material culture and find ways to think through things and do them together.

ID: What was it like growing up with architect parents?

Anda French: Architecture requires a lot of paperwork. We’d go into their office and there would be stacks of paper everywhere. I’d be like: ‘I don’t want to do that!’But we never went anywhere without talking about how people lived. The difference and sameness of how people come together to make space—that, for me, was what architecture was.

JF: But hanging out in their office after school, we could look at, for example, the abandoned Catholic school they were turning into housing, and take a field trip to its scary basement. That kind of adventure excited us.

AF: We both had to get over the idea of not wanting to set foot in an office and just do paperwork.

ID: Did academia help you get past that idea?

JF: I studied physics but then got into printmaking. I was about to apply to MFA programs and began to realize that maybe I could get a kind of architecture degree that would allow for the other things I was interested in. Academic architecture and art practice architecture are these Venn diagrams with overlaps, and we’re always trying to find the right mixture.

AF: And meanwhile I was whispering in your ear, Jenny, all these things were things we could figure out together (laughs).

ID: And you’ve spent your careers working together. Are you treated differently, as sisters?

JF: It’s really interesting that we’re often considered sisters in architecture before being women in architecture—and then I ask myself about the brothers we know: Are they ever asked about their brotherness? For us, it’s sort of on-brand with this radical inclusion of humanity and our personal lives, transgressing the boundaries of what’s appropriate and that sense of propriety over what can be included in work and what can’t. So maybe I’ll say I’m ok with it because it’s kind of central to the ways we break out of formal working relationships.

AF: We believe in design that is disarming. In a way, letting the sister thing be a thing disarms people immediately. Something we have thrived on is feeling the confidence of family, just talking and being candid. We felt comfortable together as women in architecture. We definitely have a lot of conversations about how, coming up in different ways through academic and practice models, you are discounted. You’re thought of as that young woman who doesn’t know much, and then there’s the turning point where you’re too old.

ID: Are you seeing that change at all?

AF: There’s maybe more care now in listening to women, a slight opening up of academia, particularly in the tenure track, to talk and listen and change the systems.

JF: Architecture is incredibly lacking in diversity around gender and economic accessibility and Black and Latinx presence. It is looking to make change faster, but I think it’s a little yet to be seen. As faculty, I try to model a version of practice and teaching that is not totally unsustainable and unkind. We take on projects that are just at the edge of our ability to do them entirely on our own—and that often means taking things that are not necessarily star commissions.

AF: We designed a lifestyle that then becomes a practice. We both have kids, we both teach, and so there’s a number of projects we know we can slot in. But there’s a limit. We could grow the practice, in which case we’d be more managing the work and less close to the work itself. Or we can find the fine line where we can do the actual work, find that intellectual satisfaction in a project that has the impact in the set of social issues we’re interested in, in the actual number of hours we have in a week. It’s a reverse-engineered practice that has to answer, literally, to: What do I want to be doing at 3pm on a Tuesday? Rather than a world-domineering practice we could sell to a giant multinational.

ID: How did you decide on the firm’s name?

AF: Jenny and I both have the same eye condition, a lack of depth perception. So the way we see the world, as a kind of flattened two-dimensional set of views, bonded us with a shared view of the world. The last year of being on Zoom has absolutely prompted conversations of how we share information in ways that segments of the population can’t access because of the way graphic design is deployed on screen. We have to break down architectural practice and think through making space in ways that allow us to think through who we might be designing spaces for, with all their different abilities.

ID: Which you’re doing for the Malden Cohousing community in north Boston, right?

AF: The project involves 30 households who have come together partly because some of them have disabilities and need housing to work differently. It requires conversations about breaking down elements of architecture and reassembling them in ways you might not if you’re just making a two-bedroom special.

JF: One thing that’s really important in cohousing is being able to be at your window or door and see a community. So one of the ways we’re designing the building is with a core where everything is visually accessible—you’re not running down three flights of stairs to see someone but connecting across the building in ways that facilitate social connections for people who have reduced mobility, or are babies, or are elderly. The community includes people from age 30 to 70 who intend to age in place there. So there’s an elevator but there are also nooks for resting, tactile comfort zones, wider clearances. There are very real, tactile, and disarming ways that materials and arrangements of space can become more supportive. We’re questioning very basic choreography between bodies and space and seeing how they interact to find out whether or not some of these redomesticated versions of social relationships are things we can work on as well.

ID: Talking of domestic space, what was the inspiration for the Outlier Lofts, in which you reoriented a three-story pair of connected townhouses?

JF: We love Beetlejuice and things that get at ways of imagining history as a place of slight uncanniness or creepiness. And also thinking through ideas of what preservation could possibly mean as we think about reinhabiting existing structures. So this project had a unique backstory: it lost the top floor in a fire, which meant we could add a floor and make three fairly large, new apartments in what was two row houses. We played games of taking this structure and reproportioning it. The “sawtooth” roof are off-center gables that sort of repeat, and when you come to the end it cuts off to create a sort of natural mansard. We hid the real front of the building by making it the side. The preservation world just wanted the street presence to feel continuous.

AF: It’s blocks from where we grew up and from where our office is now. It’s a strange enigma of a building—women weren’t even allowed in the [former ground-story] bar until the 80s. There was a women’s parlor. It was a mystery and getting in there and sculpting it to our own memories and imaginations to project into the world had a strange appeal…On some level, staying in Boston and operating in its different spheres is a perfect model or trying to work in architecture, in which you have to produce things that are going to be received by multiple audiences and ask people to see multiple things. We’re here having conversations with people who would never find themselves in the same room, as a hinge between them. That keeps us agile, and maybe a little confused at times, about trying to figure out what we’re after.

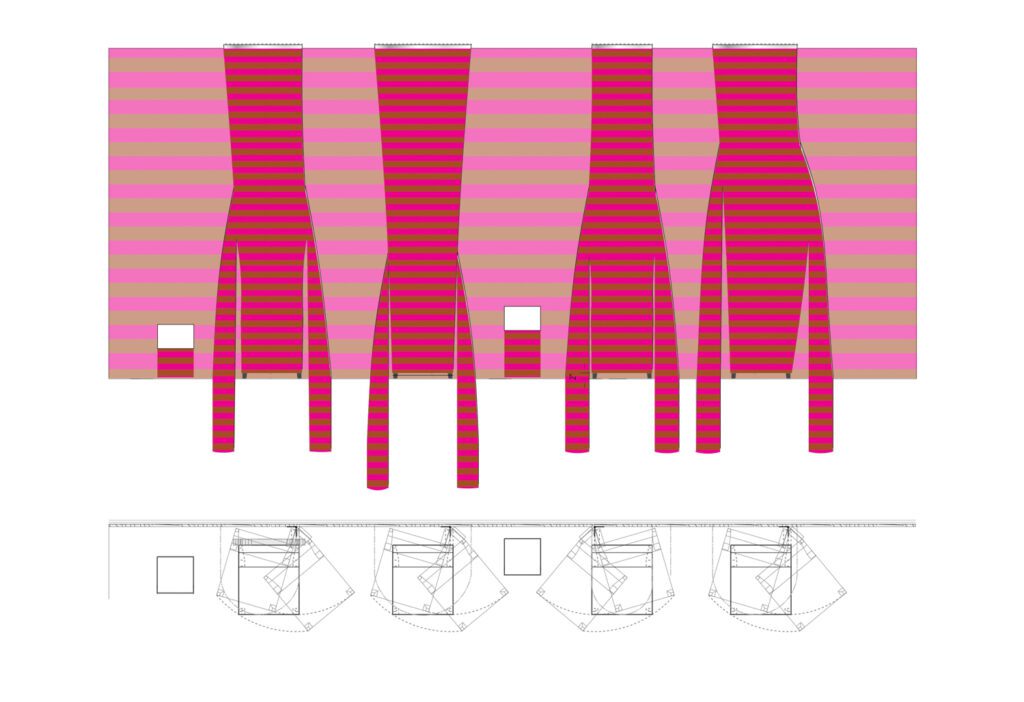

ID: What were you after in designing the Kendall Square Garage Screens?

JF: The neighborhood thought this large, open-structured garage was an eyesore and wanted it covered in something.

AF: We decided on a giant, full-scale drawing. We print up 24×36” drawings all the time, but this was alike a 24,000-square-foot one. Who wouldn’t want to do to that?

JF: Regular facades have the task of negotiating the conflicts between what the inside wants to be and how it performs as an urban image. We had the happy directive of really only dealing with the outside, but we decided the point of this gigantic object was that it both wanted to conceal itself and also stand out. It was being looked at from very different vantage points, so we worked with the idea of something not necessarily orientational but abstracted and maybe architectural in the way it produced repetition and depth. It was really triggered by the idea of who was looking at it and from where. Would they get bored, or could they keep looking at it and finding something else?

AF: How much attention does anyone have for the urban landscape in the first place? Who’s looking up at it and who’s looking down? We wanted an aura of light moving around you, an everchanging but still rigorously geometric palette.

ID: Your Cozy Wall/Wall Cozy for Harvard GSD’s Experiments Wall program also plays with the idea of activated facades—what was its inspiration?

AF: The base idea was that we could actually produce a living space rather than a presentational space. And if we were going to talk about questioning architectural thinking in the 2D and the 3D, how much can we push the envelope between what is a wall and what is a drawing? What is the body in space and what is furniture? Instead of a retrospective of our work, why not do something speculative? How do you take away your initial assumption of how you’re supposed to do interact with someone else given a moment of vulnerability in which you have to invent or figure it out together?

JF: It’s like the research and speculative projects and more narrative-based projects we’re working on, which combine existing large townhouse renovations with questions of the nuclear family and the pressing ways we could live together.

AF: We need lots of stories of ways we imagine lives together that don’t all end up in our little apartments around cities watching Netflix alone. We can find ideas to shape how we care for each other. That’s the goal.

more

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Chris Gustin

Ceramic artist Chris Gustin dives into the dynamic exploration of movement and nature in his largescale works and his show at the Donzella gallery.

DesignWire

A Career In Color: Explore Olga De Amaral’s Retrospective In Miami

Explore a different perspective on color with textile artist’s Olga De Amaral’s retrospective at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami.

DesignWire

Cheers To 200 Years Of The National Academy Of Design

To mark its 200th anniversary, the National Academy of Design presents a showcase honoring contributions to contemporary American art and architecture.