10 Questions With… Shahed Saleem

Earlier this year, architect Shahed Saleem designed a colorful deconstructed mosque pavilion for a courtyard in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. Throughout Ramadan—a period in the Islamic calendar marked by fasting, prayer, reflection—the structure offered an invitation for all to step inside, creating an accessible and inclusive opportunity to engage with faith-based design. Herein lies the message behind Saleem’s work.

As design studio leader at the University of Westminster, Saleem explores the architecture of migrant and post-migrant communities, particularly their relationship to ideas of heritage, multiculturalism, and belonging. After founding his architectural practice, Makespace, in the early 2000s, the London-based architect began consulting on planning issues facing faith and migrant communities while working on a wide array of projects. In the past few years, he has diversified his practice to include teaching, writing, research, and architectural installations.

Saleem also channeled his research into a book, The British Mosque: An Architectural and Social History, published by Historic England in 2018. Shortly after, in 2021, he created life-sized case studies of three London mosques for the Applied Arts Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Here, Saleem shares his perspective on ideas around historic authenticity in the post-colonial era, breaking out of diaspora narratives through design and the evolution of mosque architecture in the UK.

Shahed Saleem on the Architecture of Community Spaces

Interior Design: What inspired the design of the Ramadan Pavilion installed in the Victoria and Albert Museum Exhibition Road Courtyard earlier this year?

Shahed Saleem: Each element is derived from a 19th and early 20th century drawing or a photo in the V&A museum collection. So the idea is that it’s a sort of reinterpretation of that colonial period of collecting, but also a rereading of it for a contemporary use. People from here went over there to record Muslim cultures as colonized places, but now there are large Muslim communities here. It’s a sort of post-colonial encounter. The Mihrab [a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the qibla, the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying] is taken from a photograph of one in Aleppo and the Minaret is a famous photograph from the early 20th century of a 15th century minaret in Cairo. The dome is from an 1860s painting of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. So the pavilion contains different references from different places that have been reinterpreted and reassembled, creating new relationships between objects in the process, without worrying too much about historical authenticity. This idea of historical authenticity, that you have to have a scholarly approach to history, is a Western notion. But actually, when you go around the country, there are 2,000 mosques that all pull from different places and have their own approach to history and it’s fine.

ID: Why did you choose objects from the museum collection?

SS: That relates to diaspora communities and how we conceive of ourselves. Diasporas are often trapped within a narrative of themselves that is given to them through the colonial gaze so it’s much more difficult for people in diaspora situations to envisage themselves as anything different than what they’re told. You are given an impression of who you are. Like a museum gives you an impression of what your history is. How do you get outside that to imagine yourself differently?

ID: What led you to use bright colors in the Ramadan Pavilion?

SS: Color was an important thing to use, partly because it’s excluded from modernist architectural thinking. The idea is that color is often seen as too frivolous and not serious enough or childlike, and it’s about reacting against those canons of taste, which are quite exclusionary. Color also makes people feel much less intimidated and inhibited. That’s also why there was no floor or base to the pavilion, so no threshold. You didn’t have to ask yourself ‘Am I meant to go in there or not?’ It demystifies the whole thing. I think because it was in the courtyard of the museum, the pavilion also didn’t fall within any particular curatorial control. If it had been in a gallery there would have been a curator and a team that would have been keeping a much more careful eye in terms of what happens with it. I started to realize it was in bit of a no man’s land in the museum, so we could get away with it being fairly free in terms of the things it was being used for.

ID: Where you surprised about the way the pavilion was used?

SS: I think what the pavilion showed is that there is a real hunger for doing things in a new way. It was all happening in a space that was malleable and people seemed really enthused by that. It wasn’t just a mosque; it was a mosque when it was used for Friday prayers but it was also a place where people did drumming, a location for a fashion shoot, kids played on it and climbed up and down it and took pictures at the top of the Minbar [pulpit]. Some people would stand in the Mihrab and take pictures. Both men and women used it quite freely. So there was no gender separation around these elements so their religious symbolic meaning shifted. They still had a religious cultural significance but they didn’t have the baggage you might have within an actual mosque. I was pleasantly surprised by the way in which it was so easy for people to allow these symbols, which are usually quite specific religious symbols, to change meaning.

ID: How did your interest in British mosque architecture come about?

SS: My mum started a mosque in Catford, Lewisham, in southeast London, when I was young, so I was always involved in mosque activities and helping her organize community events. In my teens, my parents bought a house that they converted into a mosque. There was a group of people doing the fundraising so I was seeing cultural reproduction being self initiated from an early age. When I set up my own practice I started getting approached by mosques locally. I think people came to me because I had a familiarity with the whole process and could relate to what people were trying to do.

ID: What characterizes the British mosque; is there a British mosque vernacular?

SS: I think it has had different periods. From the late ’70s to the ’90s, it was a composition of different parts where you have bits of architecture that relate to local or domestic vernacular materials, like the brickwork or tiled roofs, or windows that could look quite residential. Then these get combined with elements that are Islamic replicas of domes, minarets and arches. In that period you got these quite interesting compositions and amalgamations of different architectural references, which I always found quite intriguing because there is a unique language that emerges from that. From the mid-’90s and through the early noughties you start to get a more Islamicized and historicized image emerging in buildings that were built from scratch but the language is of a historic mosque type building. This was quite a historicist phase. I liken it to the Gothic revival, the period when Pugin was recreating medieval Christian architecture. I think we are still in this phase but it is loosening up gradually and there are proposals for more contemporary, exploratory or experimental designs.

ID: Can you tell me about your V&A special project at the Venice Biennale in 2021, in which you explored the undocumented world of adapted mosques through three existing mosques in London. What sort of feedback did you get?

SS: We were focusing on the mosque in Britain as self-made community architecture and the creativity that comes out of that, the new types of visual culture and architecture. There was a lot of positive feedback, a lot of second generation Muslim people in the U.K. who didn’t realize that their lived experiences were significant enough for this kind attention and exhibition, so they were very moved by that. We also got feedback that the exhibition countered orientalist depictions of Islamic art and culture as medieval and historic craft by instead presenting everyday lived realities.

ID: You also paint and draw and sketch. What does this bring to your practice and research?

SS: I think as an architect or designer, you are always exploring visual language, it’s almost a compulsion to do so. It’s a form of inquiry and a form of processing what you see or think. A lot of my pieces are spatial or architectural in some way, and it’s often places I might have visited or seen or remembered that are particularly interesting architecturally or spatially. Sometimes I might have been doing drawings in a particular way, and then there might be a project down the line where I think the way I did those drawings is something I can bring into the project. I mainly draw in sketchbooks and then some stuff on separate bits of paper. It’s also about playfulness really. I think the idea of play is important, because you discover things you wouldn’t necessarily discover otherwise.

ID: For the Folkestone Triennial in 2021 you created a lantern installation and exhibition display at the local mosque alongside artists Hoy Cheong Wong and Simon Davenport. You hosted a series of workshops with local children who attend the mosque. What was that about?

SS: The idea of the workshops was about looking for a visual language that feels embedded within the experiences and histories of Muslim people in Britain. It’s a kind of visual language that reflects the experience of being diasporic and Muslim diasporas. The ongoing question is how does one do that without being trapped within these visual historic references of the Islamic past? The drawings that the kids did were adapted and I reworked them into a particular pattern that then also became the pattern module for the facade of the building.

ID: What do you think the next phase of mosque architecture might be in Britain?

SS: We’ve all been sitting around thinking what should the architectural language of the mosque should be. Perhaps we can take something historic and do something abstract with it? Or maybe let’s take this piece from a pattern and create a more contemporary interpretation of it? But in a way that’s still just playing around with form. Having seen what happened with the Ramadan pavilion, it makes me think that innovation in mosque design will come through a new form of use. That’s the next stage, for the actual programme, function and social meaning to evolve, and that will drive a more meaningful next architectural step. So I feel the next stage of what the mosque will be architecturally is going to be programme led.

read more

DesignWire

8 Biennale Installations Explore the Social Impact of Architecture

The 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale considers themes of inclusion and the built environment. Explore these eight memorable, immersive installations.

Projects

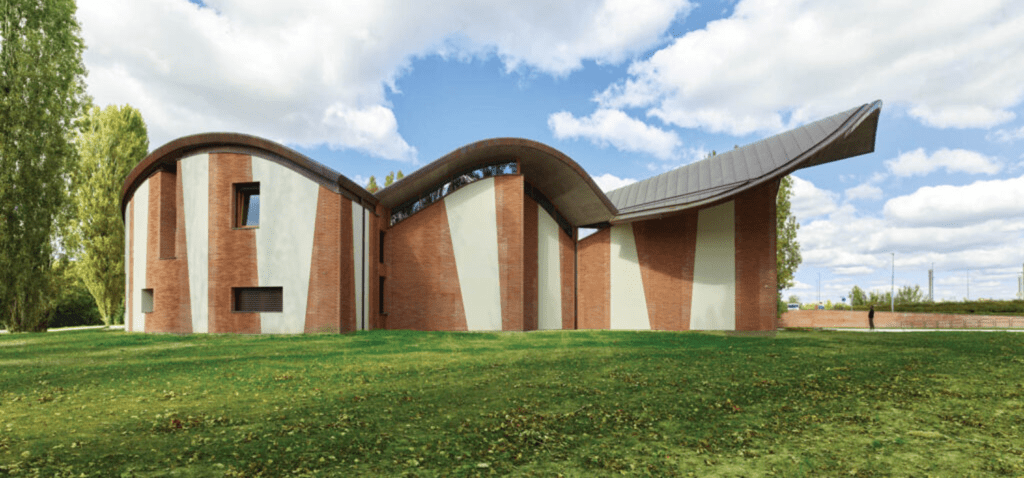

Benedetta Tagliabue-EMBT Designs a Contemporary Church in Northern Italy

A growing congregation in northern Italy is blessed by San Giacomo Apostolo Church, a new complex by Benedetta Tagliabue-EMBT that’s both contemporary and contextual.

Projects

For a War-Torn Region, This Modular Building Serves as a Community Haven

These portable blocks by Kiev-based studio Zikzak are part of a modular building system to provide crisis structures for Ukraine.

recent stories

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Jonah Markowitz, Production Designer For HBO’s New Crime Thriller

Ride along with Jonah Markowitz to see how this production designer effortlessly builds immersive worlds for projects like HBO’s Duster.

DesignWire

Pierce Brosnan’s Enduring Passion Takes Shape In New Porcelain Series

See how James Bond actor Pierce Brosnan teams up with designer Stefanie Hering to produce a handcrafted collection of vases with proceeds going to charity.

DesignWire

Interior Design Hall of Fame Members: View by Year

From the past to the present, meet the celebrated names and trailblazers who have all been inducted into the Interior Design Hall of Fame.