10 Questions With… Stephan Schütz of gmp Architects

When it comes to designing concert halls and performance spaces, Stephan Schütz, executive partner of gmp Architects, knows acoustics are paramount. Before turning to design, Schütz aspired to become a musician, studying piano for years, which leads him to approach each project with an innate sensibility for sound. He also seeks advice from acousticians, musical directors, and conductors of renowned symphony orchestras who will be using the spaces he creates. Such research leads to lasting partnerships with the likes of lauded acousticians, including Yasuhisa Toyota, as well as Frauke Roth, general manager of the Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra.

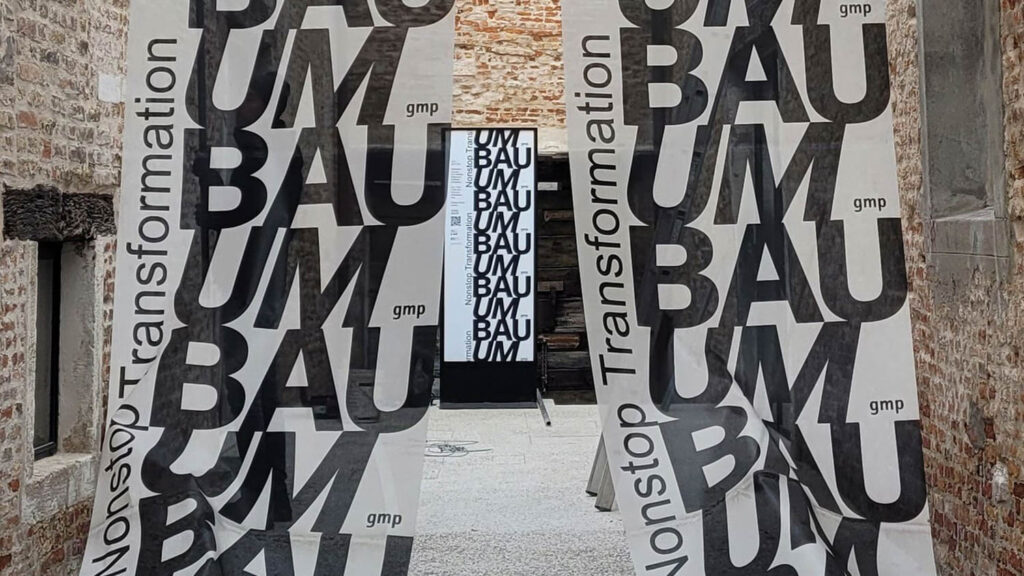

Well versed in the nuances concert hall design, Schütz welcomes the challenge of transforming existing structures into modern venues, centering his work on adaptive reuse. An exhibition honoring such spaces designed by gmp Architects, which is based in Berlin, opens at the Goethe Institute in Manhattan October 9, 2024.

Schütz’s work on the Isar Philharmonic in Munich will be exhibited as part of show aptly titled “UMBAU.Nonstop Transformation,” which debuted in Venice, Italy, in 2023. In German, umbau translates roughly to ‘reuse’ or ‘conversion,’ referencing the ongoing transformation of existing structures. The New York show will also include the Kulturpalast Dresden, home of the Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra, a city library, and a noted black-box cabaret venue featured in the film Tár, as well as other notable spaces.

Prior to the New York show opening this fall, Schütz talked with Interior Design about his love of music, learnings from acousticians, and the growing appeal of modular concert venues.

Get To Know An Architect Of Sound, Stephan Schütz

Interior Design: As an architect, your work often centers around concert halls. How did your interest in sound and designing for sound-focused spaces develop?

Stephan Schütz: As a child, I played the piano with great enthusiasm. I wanted to become a musician, a conductor to be precise. While playing the piano together with the chief conductor George Alexander Albrecht during an internship at the opera house in Hanover, he told me that I should better keep my love of music alive but perhaps concentrate on a different career path. And it was precisely this conductor that I met again 20 years later when I was allowed to design and realize my first concert hall for gmp architects for the Staatskapelle Weimar. At that time he said to me: “Look, I gave you the right tip. You have a great job that has led you to music.“

ID: What about design more broadly; what led you to pursue a career in architecture?

SS: Let’s stay with the comparison to music for a moment. As an architect, you are a conductor in the sense that you have to bring together different parties involveld in the constructions process to create a whole. The architect is the specialist for the whole, a generalist, so to speak.

ID: Let’s talk about gmp Architects’s October show at the Goethe Institute in New York. Could you share more about the adaptive reuse projects that will be on display?

SS: The exhibition “UMBAU. Nonstop Transformation” was presented with great success at last year’s Architecture Biennale in Venice. This year, it will be shown in Hamburg, Berlin, New York, and Shanghai. Our aim is to convey that, in times of climate crisis and dwindling building resources, we should use what we have. The exhibition conveys that we do this with great joy and respect for the buildings that others have designed and built, be it the transformation of a former steel factory into the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts or the conversion of the Santiago Bernabéu Stadium in Madrid, which had to be carried out while the stadium was in operation.

ID: Transforming historic structures into modern performance venues seems to be your forte. What do you find most exciting about these projects?

SS: In contrast to freelance artists, we architects work within complex contexts, also constraints of an economic, social and ecological nature. These interrelationships form the framework of our work, which is particularly evident in the construction of existing buildings. Before we make any design decisions, we have to explore and understand the buildings we are working with in detail. This almost archaeological preliminary work is incredibly exciting, also because it holds a lot of unexpected things in store. And creating something on this basis that future generations can use and benefit from is an amazing socially responsible task.

ID: What have you learned from acousticians and musicians about designing spaces for sound?

SS: The decisive factor for the quality of a sound space is that the visual impression is as congruent as possible with its acoustic behavior. We expect a high church room to have a long reverberation time. If this very room sounded dry, we would be irritated and feel uncomfortable in a certain way. This means that room shape and volume, but also materiality, must be brought into balance with the sound behavior.

ID: What challenges have you encountered when retrofitting performance spaces within historic buildings, like you did for Kulturpalast Dresden?

SS: The Kulturpalast is a listed building from the sixties of the last century, which stands in the middle of Dresden’s baroque city center as a testimony to modernity. The challenge was to preserve the identity of the building and integrate completely new functions inside. The result was a library and, at its core, a completely new, top-class concert hall, made famous by the film Tár, whose visual appearance reflects the warm, dynamic sound of the Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra.

ID: How did you arrive at the design for the Isar Philharmonic in Munich, which includes a modular concert hall?

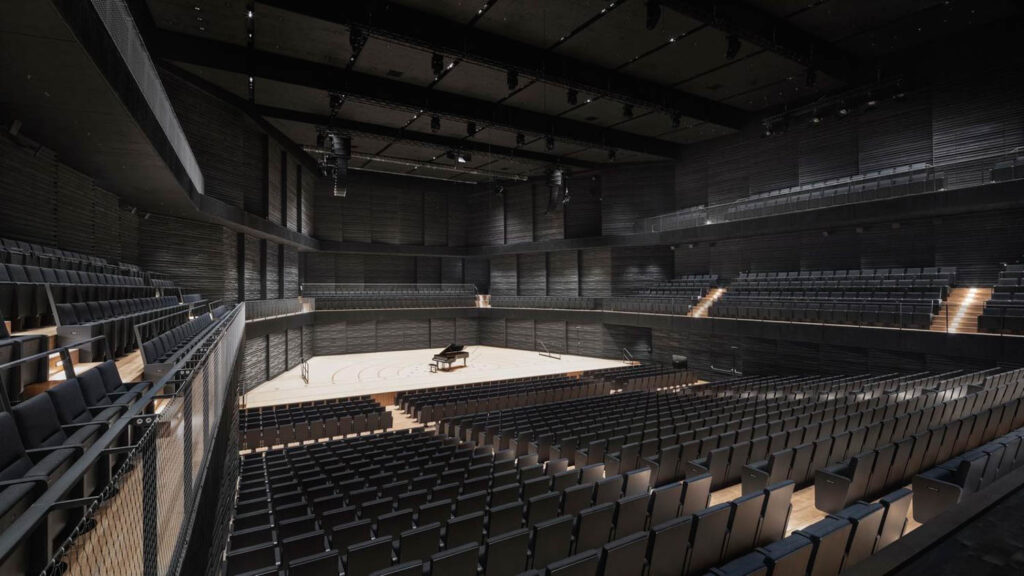

SS: The task in Munich was to create a temporary venue for a period of five years for the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, whose concert hall needed to be renovated. In this context, we found a former transformer hall from the 1920s, in which we housed foyer areas, checkrooms and a library, and to which we added a concert hall of roughly the same size as a twin building right next to it.

ID: In what ways does a modular structure impact sound? What are the benefits of such structures from an acoustic perspective?

SS: Due to the originally planned short service life, together with Yasuisha Toyota from Nagata Acoustics—who was also responsible for the acoustics of the Disney Music Hall in Los Angeles—we chose a construction method that is almost completely modular and could be rebuilt elsewhere. This consists of 15 m high and 30 cm thick cross-laminated timber walls, which are interlocked like scales with easy-to-remove connecting elements. The special thing about it is that we have avoided any cladding, as is normally the case with concert halls, so that a simple, inexpensive and quick to erect structure has been created. When it opened, the Isarphilharmonie impressed the experts, the audience and, above all, the musicians so much that, to our surprise and contrary to all considerations of modularity, it was immediately decided not to dismantle the hall but to leave it in place.

ID: Do you envision modular concert halls as a prototype for the future? In other words, could such spaces become traveling components that move with a particular orchestra; i.e. spaces designed for specific rather than universal sounds?

SS: In view of the enormous need to renovate theaters, operas, and concert halls that were built before and especially after the Second World War and are gradually awaiting complete refurbishment, I believe that we will see a great demand for temporary cultural buildings. The Isarphilharmonie demonstrates that cultural buildings do not automatically have to be expensive or take a long time to build. And it is precisely the simple and robust construction method that appeals to younger generations who are interested in music and culture.

ID: Is there a dream project you’d like to work on?

SS: Believe it or not, the dream projects are on the drawing board. The conversion of the State Library by architect Hans Scharoun is one such project, and the renovation of the famous Natural History Museum in Berlin will keep us busy for many years to come. And if we succeed in designing a cultural project in the USA as a result of the exhibition in New York or other activities, that would certainly be the fulfillment of a personal dream for me.

read more

DesignWire

Design Reads: A Closer Look at Jasper Morrison’s Work

Discover British designer Jasper Morrison’s wide range of furnishings, homes, and housewares in his cheeky retrospective “A Book of Things.”

DesignWire

Eco-Friendly Pavilions Take The Stage At A Chinese Music Festival

For a Chinese island music festival, Also Architects crafts reusable, modular pavilions that provided shade while resembling sound waves.