Bauhaus Protégé Richard Filipowski Gets His Due

In an imaginary snapshot, capturing the many achievements of designer, artist, and educator Richard Filipowski, he would appear on two of modernism’s greatest U.S. stages, Chicago and Boston, in the company of many of the mid-century era’s greatest actors: his mentor, László Moholy-Nagy, in addition to Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and Buckminster Fuller, to name a few. Meanwhile, in the memories of generations of architecture and design students, Filip, as he was generally known, was a gaunt, slouching figure. But it is only after his death, in 2008, that his art has been gaining national and international attention, beginning in 2013 with the first New York solo show of his work—a show I coproduced at the Hostler Burrows gallery.

In an imaginary snapshot, capturing the many achievements of designer, artist, and educator Richard Filipowski, he would appear on two of modernism’s greatest U.S. stages, Chicago and Boston, in the company of many of the mid-century era’s greatest actors: his mentor, László Moholy-Nagy, in addition to Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and Buckminster Fuller, to name a few. Meanwhile, in the memories of generations of architecture and design students, Filip, as he was generally known, was a gaunt, slouching figure. But it is only after his death, in 2008, that his art has been gaining national and international attention, beginning in 2013 with the first New York solo show of his work—a show I coproduced at the Hostler Burrows gallery.

Hostler Burrows went on to display Filip’s sculptures and/or paintings at Design Miami/Basel, the Salon Art + Design in New York, and Fog Design + Art in San Francisco. And design journalist Marisa Bartolucci, whose father was Filip’s classmate in the 1940’s, is in the process of editing Beyond the Bauhaus: The Art and Design of Richard Filipowski. I am also contributing to this substantial monograph, which should burnish his reputation if not help elevate him to marquee status.

The timing of the book is propitious, coming on the heels of the blockbuster “Moholy-Nagy: Future Present” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Among Moholy’s favored students at Chicago’s Institute of Design, Filip absorbed the Bauhaus method: relentless experimentation with materials; daily exploration of form and space, light and void, and modular structure; and the constant posing of design problems and quest for their solution. The summer after graduation, he became the only student Moholy asked to teach there.

A handful of Filip’s undergraduate projects found their way into Moholy’s seminal Vision in Motion. From an architecture course came a space modulator, a device for showing how light and shadow shape perceptions of an interior volume. Multiple experiments in extracting forms from sheet material yielded an aluminum sculpture that Moholy chose as well. (It then inspired a sculptural chair, cut and bent from a single sheet of plywood, that Filip submitted to the Museum of Modern Art’s International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design.)

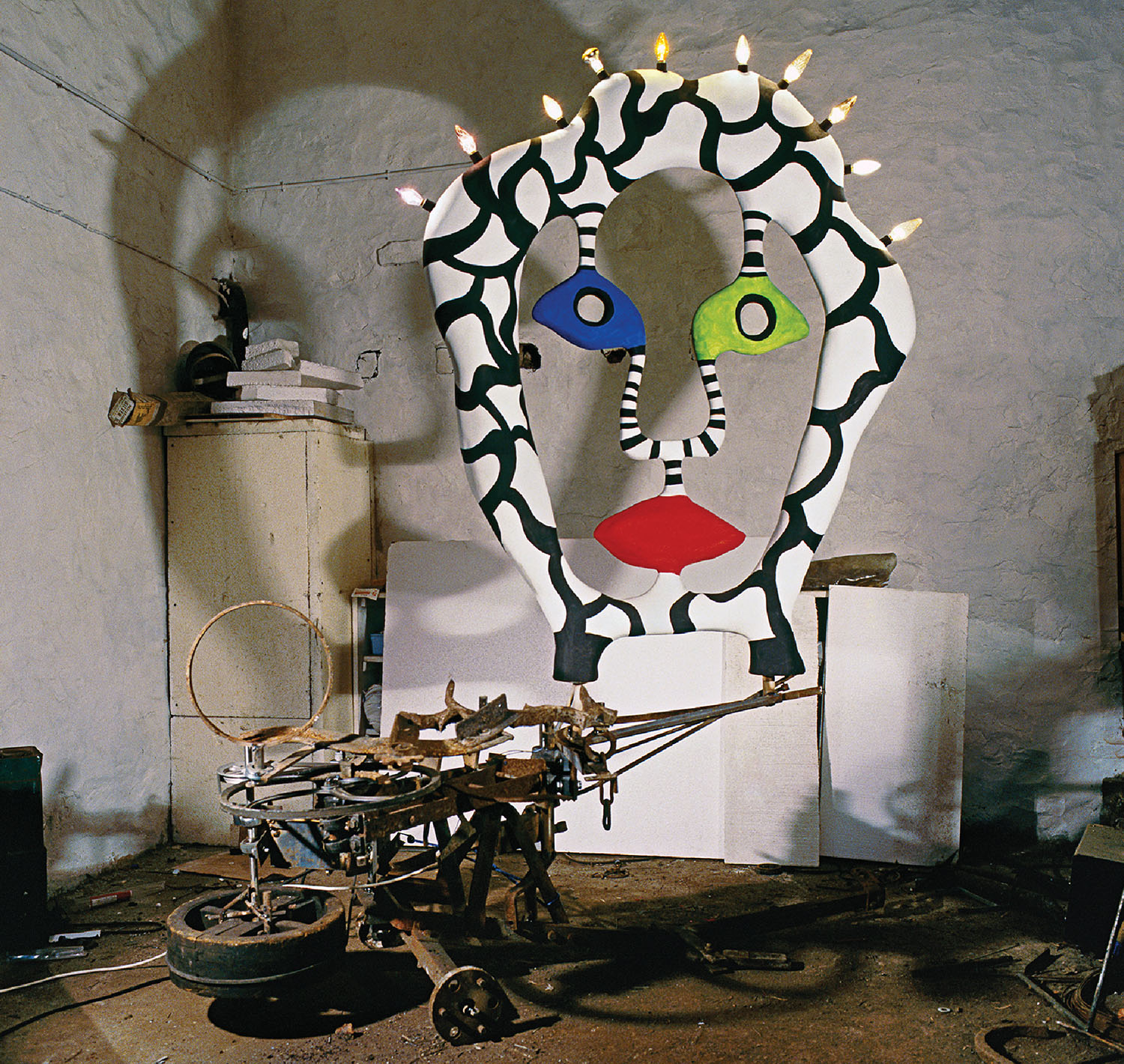

Moholy lauded an acrylic chess set by Filip both for its transparent beauty and because the shapes of the pieces indicated their moves, and New York’s Julien Levy Gallery subsequently featured the set in “The Imagery of Chess,” alongside contributions from Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Alexander Calder, and Isamu Noguchi. Filip then used a checkerboard pattern on a sideboard that he designed for his own house in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There is also a painted paper maquette for a sculpture that, never realized, would make a striking decorative screen in a house today.

His creative output was always prolific and varied, in accordance with Bauhaus precepts. In architecture, he entered a competition for a dormitory at Smith College in Massachusetts—winning an honorable mention even though he was still a student. (The Architects Collaborative, led by Gropius, won the commission.) Filip’s furniture designs include work stools with a pleasantly chunky tripod form reminiscent of Charlotte Perriand. His early paintings shared with Moholy’s a well ordered constructivism with a graphic punch that’s compared to Swiss poster art by monograph contributor Janet Koplos. She notes the often meticulous and exacting background pen work, a labor of love rather than efficiency.

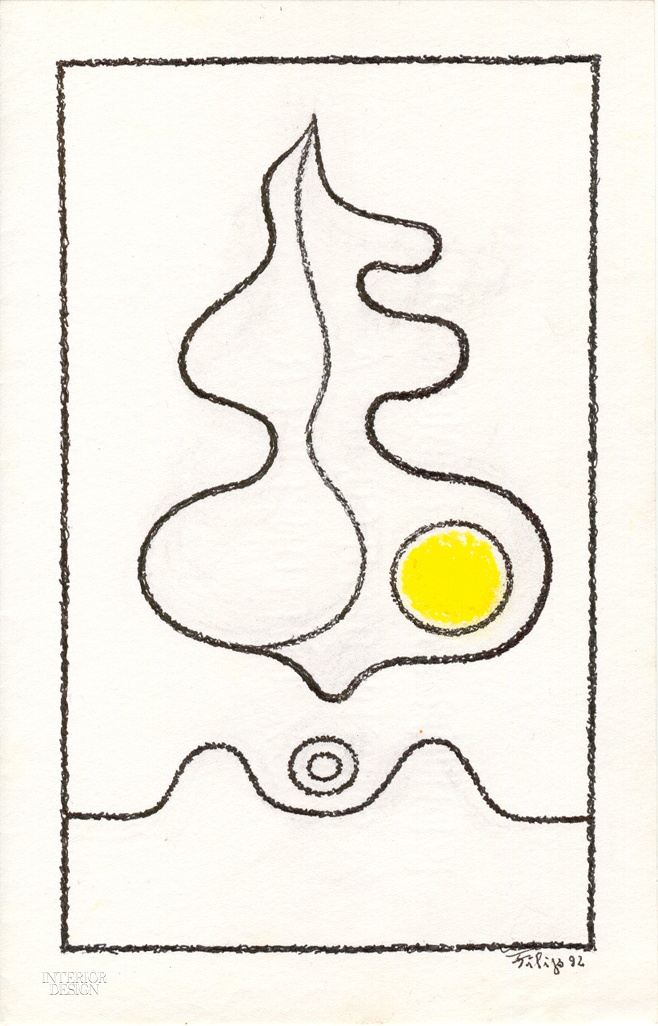

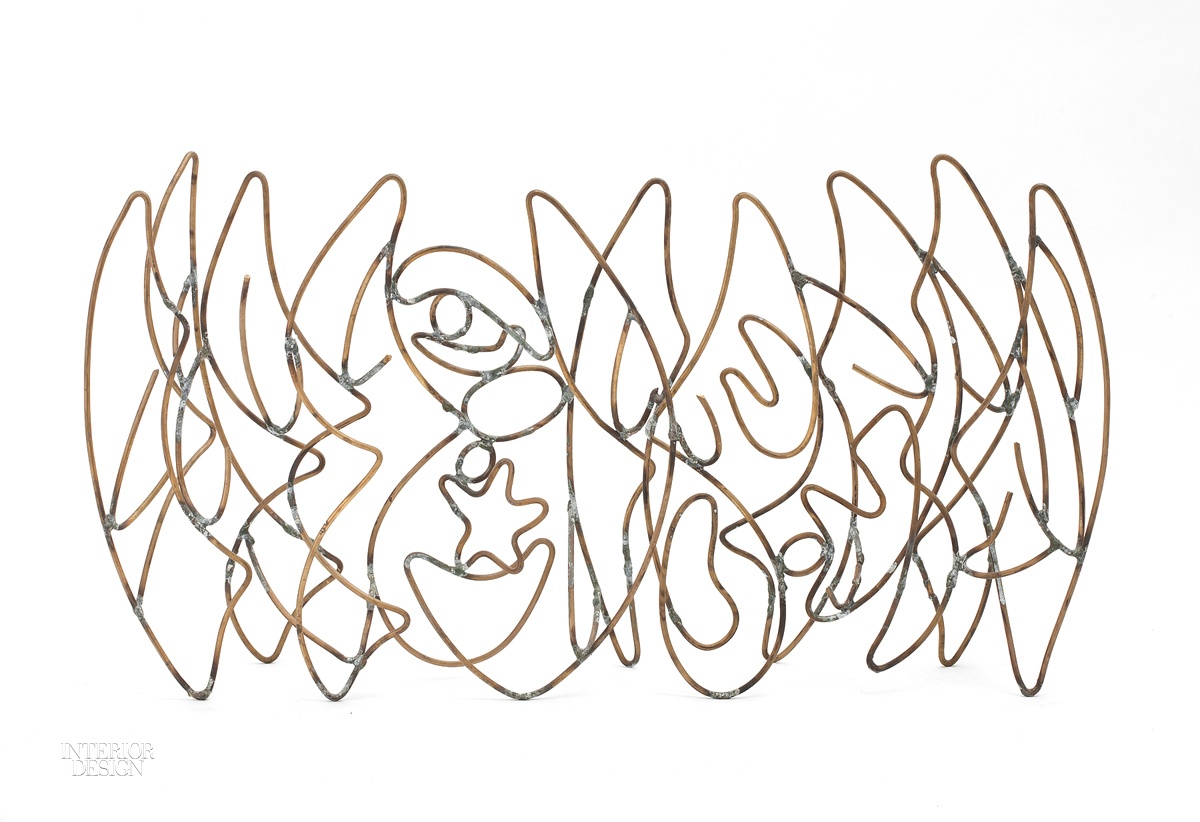

This intricate handwork carried over to his large idiosyncratic bronze sculptures, amalgamations of smaller twiglike pieces. Koplos considers the lushly vegetative forms to have “an elegance and a kind of bristly grace.” Later in life, Filip returned to two-dimensional work, revisiting earlier themes in small drawings that he termed his Pub series. Yes, done at a bar!

He saw drawing, painting, and sculpting as “the art of the psyche,” inward-turning activities in pursuit of self-exploration rather than academic acclaim or monetary reward. Teaching and writing are what turned him outward, first to his students and then to the larger culture. He taught design fundamentals courses at the Institute of Design, then at the Harvard Graduate School of Design at the invitation of Gropius, and finally at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for 36 years, until retirement. Richard Dattner of Dattner Architects, one of Filip’s star pupils at MIT in the 1950’s, recalls that he was an in-cisive if often gruff critic, given to challenging and provoking his students.

Visual literacy was as important to him as verbal literacy in understanding the world and functioning in it. He spoke and wrote eloquently about the importance of art as an integral part of education and citizenship. In a 1969 lecture, “The Art Phobia in Our Society,” he lobbied for art instruction in secondary school and for public galleries in every town, arguing that greater daily contact with art and design would improve the skills needed to judge the built environment and, more important, to apprehend the emancipating and unifying potential of art.

It goes without saying that this injunction is as relevant today as it was then. This might indeed be a good moment to rediscover a gifted polymath.

> See more from the Spring 2017 issue of Interior Design Homes