Revolutionary Science Makes Its Way into Flooring Design

At the Gropius Bau exhibition center in Berlin last summer, visitors walked into a pitch-black room, unable to see their own hands in the darkness. Upon entering the installation, many emitted audible gasps—not from the absence of light, but from the surface below their feet. Stepping into a bed of sand produced a stark contrast from the solid floors throughout the exhibition center. As the doors closed, blinking lights cut through the darkness like stars and overhead speakers played a recorded narrative about the future.

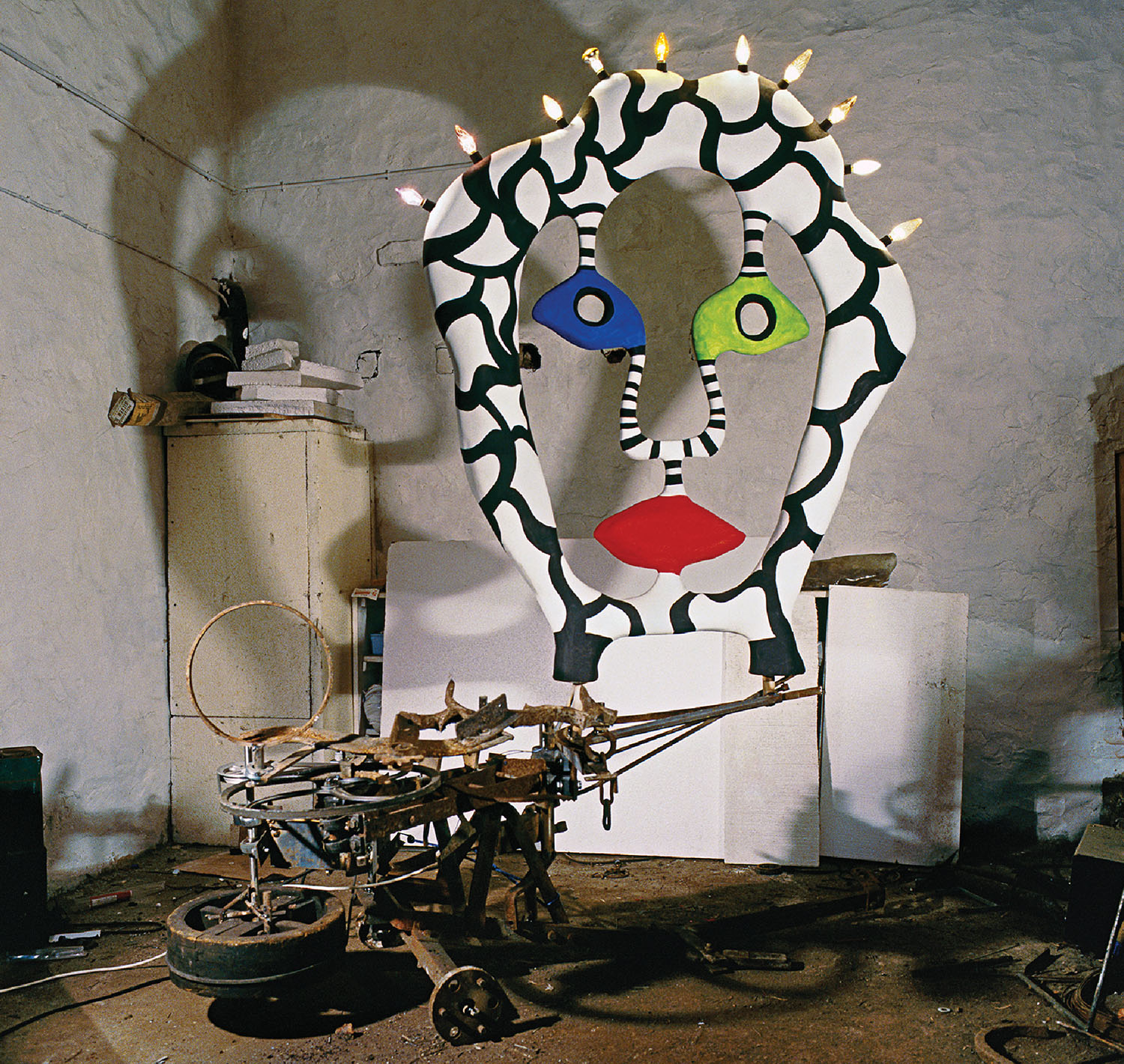

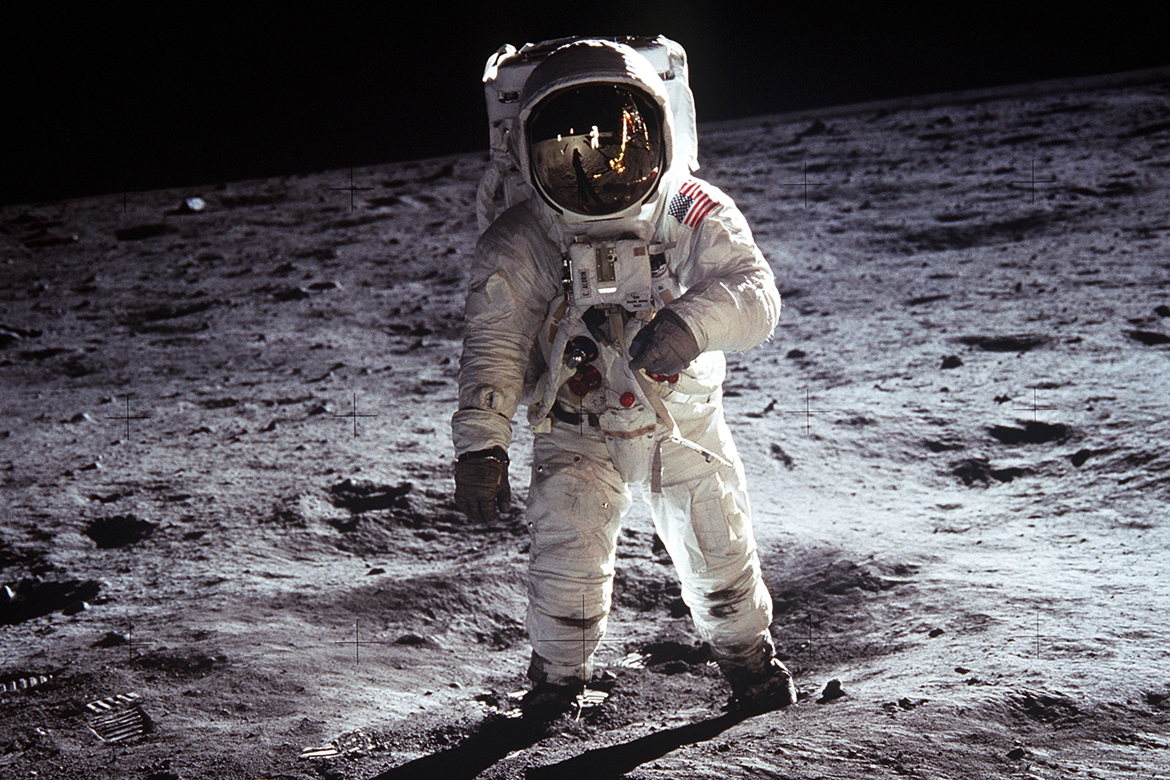

The Cosmodrome installation, created by artist Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, used black sand, light, and sound sequences to create this intergalactic environment. Most experiencing Cosmodrome instinctively associated the materiality of soft grains beneath their feet with outer space, largely due to video footage and images of the moon’s powdery surface ingrained in memory from an early age.

Materials, natural and manmade, undoubtedly shape our perception of the world and our existence in relation to it. Our first sensory experiences trigger physiological reactions. Objects we touch influence the way we feel even after the sensation fades, according to neuroscientist David Eagleman who collaborated on the text Tome One: Haptic Brain in the book, A Communicator’s Guide To The Neuroscience of Touch. In the work, scientists note that more than half the brain is devoted to processing sensory experiences. As humans, we have a vast innate ability to form deep connections with anything we touch, see, hear, taste, and smell.

Haptics—the science of touch—along with all the other sensory inputs can be influential tools, offering designers exciting possibilities when deciding which materials to use in a space. As workplace design shifts to prioritize more human-centric spaces, our approach to these environments morphs, too, says Mindy O’Gara, director of product and learning experience at Interface. Now more than ever, we’re understanding through neuroscience that we have the opportunity to forge memorable connections to materials creating more meaningful experiences with the built environment. “One of the first sensory connections we have is to material,” says O’Gara. “Our emotional interpretation of the materials that surround us inform how we feel about a space and whether or not we’ll use it. Is it appealing? How does it engage or behave? Can it shape to specific needs? All of these qualities are very important when we think about the value and depth of materials.”

One solution is to seek out adaptive products with timeless design elements. Careful consideration during the specification phase for the essentials of a space—i.e. flooring—holds the potential to greatly shape an occupant’s experience. This is largely because elements of a room often inform the perception of other textures, colors, and shapes throughout it. A red patch in a carpet appears as such only in relation to the elements around it, explains French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty his book Phenomenology of Perception. He goes on to write: “This red patch which I see on the carpet is red only in virtue of a shadow which lies across it, its quality is apparent only in relation to the play of light upon it, and hence as an element in a spatial configuration.” In other words: what can we extract from the built environment based on individual experiences?

When outfitted with the right tools, such as materials with deeply ingrained associations, designers have many options. “How we perceive a space, and the materials that compose it, effects our understanding and contributes to our experience—our reality,” says O’Gara. “Our sensory engagement, down to the products we make, is pretty influential considering we activate multiple senses at once. For example, it’s easy to think we encounter a tactile material with only one sense, but the reality is we don’t just feel texture, we see and hear it.” Interface’s latest luxury vinyl tile (LVT) and carpet flooring collection, Look Both Ways™, exemplifies this by reimagining the cool edge of concrete and speckled familiarity of terrazzo—materials that, in their raw forms, pose a challenge for designers in terms of durability, cost, and usability.

Look Both Ways, created by Kari Pei, VP of product design at Interface, speaks for itself. It succeeds in exploring the interplay of sensory connections, duality of materials, and design concepts that when melded together form a cohesive whole. Collections that spotlight ideas such as these give designers freedom to create continuous patterns in two surface types or unique aesthetics that draw on contrasting textures and colors. Adding hard and soft surfaces to a space broadens the sensory experiences of those within it. This is especially true when such materials are designed to challenge the eye—observing the grit and dimension of concrete on a smooth surface, like the LVT products in Look Both Ways, comes as a surprise. “We deliberately moved away from a polished concrete look; we wanted a grittier, dimensional look that evokes an urban feeling. We achieved this through illusions in surface texture when perceived by the eye, yet are completely flat to the touch. This play in duality solves for many design attributes, from providing visual interest to facilitating easy maintenance,” says O’Gara.

As designers seek out innovative flooring materials, the environmental impact of each product no doubt influences their decision. Carbon-neutral products, like Look Both Ways, offer the ultimate solution, giving designers freedom to create an environmentally-friendly, unique flooring aesthetic that doubles as a sensory feast.