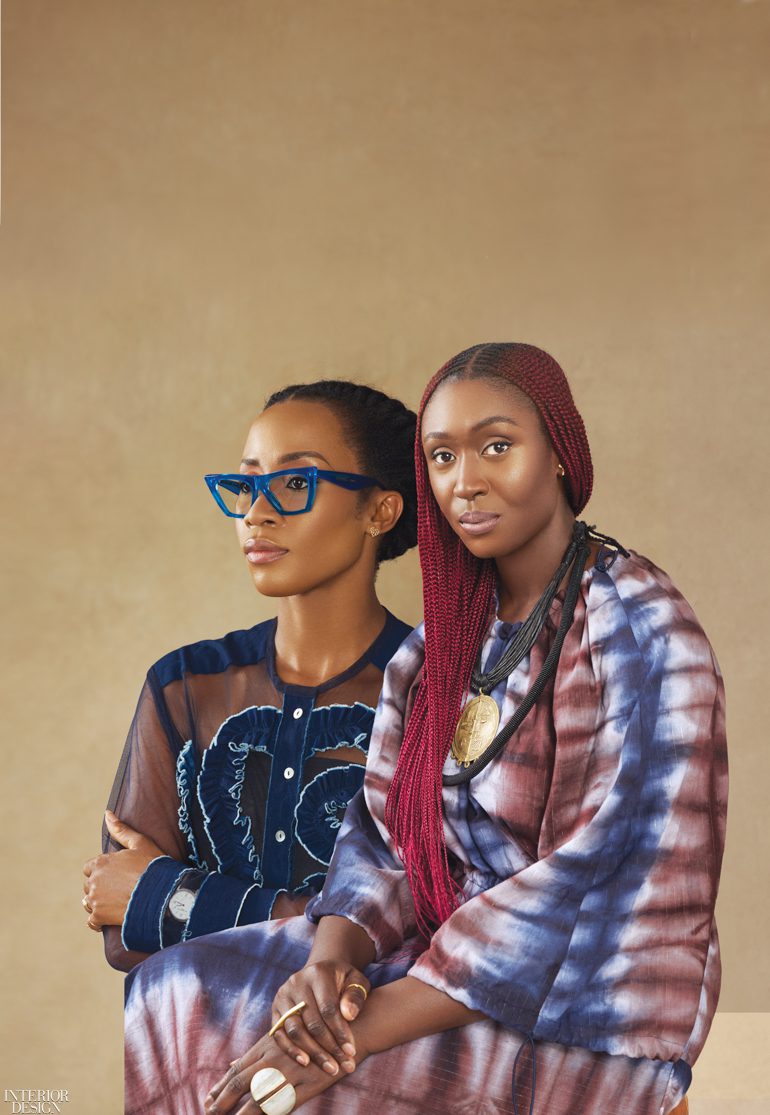

Tosin Oshinowo and Chrissa Amuah Launch Collection of Conceptual Headpieces

COVID-19 has turned the mask into a must-have accessory in

the West. But face coverings have long been a form of expression in Africa. Freedom to Move, a collection of conceptual headpieces launched in December as a Lexus-sponsored digital experience coordinated with Design Miami/, taps into that rich tradition while protecting the wearer’s eyes, nose, and mouth. It’s a collaboration between Tosin Oshinowo and Chrissa Amuah, who met a few years ago through a mutual friend, Nigerian designer Damola Rufai, and both head design practices that celebrate their African heritages. After receiving architecture and urban design degrees from London’s Kingston University and Bartlett School of Architecture, Oshinowo returned to her native Nigeria and is now based in Lagos, where

she founded cmDesign Atelier, an architecture consultancy, and Ilé-Ilà, a furniture brand. Born in the U.K. to a family with roots in Ghana, Amuah earned a textile degree at the Chelsea College of Arts and Design in London before founding her studio, AMWA Designs, there. Their Freedom to Move collection comprises three styles—Egaro, Pioneer Futures, and Ògún—in various iterations that blend 3D printing; traditional metal casting; materials like bronze, leather, and acrylic; and hand-beading, laser-etching, and West African–style embroidery. The women, who worked both virtually and in-person in Lagos, where some pieces were fabricated, tell us about the process.

Interior Design: What drew you to the idea of face shields?

Tosin Oshinowo: The brief was to create an object of our times. From the very beginning the idea of the African mask was strong in our minds. So many diverse cultures and languages exist in Africa, but what’s very uniform across all is the of symbolism of the face. With that—and the need to protect the eyes, nose, and mouth to help stop the spread of the virus—our approach was clear.

ID: Two of the masks have African names, Egaro and Ògún. What

do they mean?

Chrissa Amuah: Egaro is an ancient site in what is now Niger that was recently shown to have created its own metal technology some 5,000 years ago. Formerly, the technique was believed to have come from Asia and the Middle East, so it was great to reference that African innovation.

TO: Ògún is a Yorùbá god of war and iron. Chrissa’s dream was to visit Benin

City in Nigeria where they do traditional

bronze casting utilizing the lost-wax method. Carbon dating revealed that some old sculptures went back to the 12th and 13th centuries—such advanced technology for its day. We had a fifth-generation bronze caster use this ancient technique for the rims of the Ògún mask.

ID: One of the headpieces appears to

conceal the wearer’s face.

CA: It’s an acrylic visor finished with a reflective bronze film, the same technology as sunglasses. There’s a fractal—

a geometric pattern that repeats infinitely on ever-diminishing scales—laser-etched onto the shield. We looked at African fractals, from braided hairstyles and kente cloth to counting systems and settlement design. They are also found in nature—the network of veins in our lungs, for example. Since we were exploring air and breathing, adding a fractal pattern made a lot of sense.