7 Japanese Artists Put a Contemporary Spin on Craft Materials

In the hands of seven Japanese artists, traditional craft materials and techniques take a contemporary turn.

If Japanese traditional bamboo work has moved from being a folk craft into

a recognized contemporary art form, then Nakatomi Hajime (b. 1974) is one of the leaders of the evolution. Bamboo has a special place in the culture and rituals of Japan, symbolizing vitality, prosperity, and courage. For centuries, the country’s bamboo artisans have crafted exquisite baskets and other everyday utensils using techniques passed down from generation to generation.

The work Nakatomi produces in the southern city of Taketa couldn’t look more different than those conventional objects, however. His language is singular: geometric, architectural, almost modernist. He achieves daring forms by approaching the medium with reverence but also with a fresh mindset that’s not afraid to experiment with the unknown, employ unconventional methods, and adopt new eco-friendly dyes and lacquers. Nakatomi’s ingenious and sophisticated work straddles the line between the traditional and the contemporary, between art and craft.

A native of Kyoto, ceramicist Hashimoto Machiko (b. 1986) creates sculptural vessels that look like enormous blue-and-white flowers. Working at her home studio in the old imperial city, she uses two fundamental materials: semi-porcelain (commonly known as ironstone) and cobalt-oxide glaze. For her, blue not only is a favorite color but also symbolizes aspects of life: water, sky, and ocean. In her ceramic objects, Hashimoto recreates nature, not in a realistic way—these are not delicate blossoms—but as an abstract, imaginative, and substantial presence. While relying on the Japanese tradition of blue-and-white porcelain, her language is personal, idiosyncratic, and generative. A graduate of Kyoto Saga University of Arts, she produces powerful, expressive work that is labor intensive. Carved inside and out, and fired twice, each giant bloom is unique and takes months to complete. Most remarkably, Hashimoto manages to imbue her sculptures with a palpable sense of both serene calm and furious motion.

Clay is but one medium among many Kawai Kazuhito (b. 1984) utilizes in his highly distinctive work. His creations are odd and edgy, yet so compelling that when he exhibited them at Design Miami for the first time last December, they immediately captured the attention of collectors. After graduating from London’s Chelsea College of Arts in 2007, Kawai completed his studies at Kasama College of Ceramic Art in his home prefecture of Ibaraki, where he currently lives and works. He belongs to a generation of young artists who began with conventional ceramic craft but have turned their backs on many wabi-sabi concepts—simplicity, economy, modesty—to produce bright-hued, dysfunctional objects with powerfully eruptive surfaces. Combining sensuality with vivid color, Kawai’s work reflects a contemporary interest in the aesthetics of the grotesque, which is explored through an exceptional approach to materiality. Resembling flamboyantly irregular candy, his pieces may look like fun, but they incorporate covert critiques of pop culture, fashion, and society.

In creating The Gate, a site-specific installation at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2017, Tanabe Chikuunsai IV (b. 1973) helped bring contemporary Japanese bamboo artistry, which infuses traditional craft with radical innovation, to an international audience. As the fourth generation in a long line of distinguished bamboo artisans—previously known as Tanabe Shochiku, he was bestowed with the family’s artist-name Chikuunsai, meaning “master of the bamboo clouds,” three years ago—he is acutely aware of the central place the spirit of tradition holds when working with the time-honored material today. A graduate of the Tokyo University of the Arts, he trained in the bamboo crafts at a special school on the island of Kyushu, before setting up a studio in Sakai, his hometown. Tanabe’s pieces cross the boundaries between sculpture and architecture, while his dramatic, organic, twisted forms have become an evocative trademark.

With works in the permanent collections of some of the world’s finest museums, Fukumoto Shihoko (b. 1945) is one of Japan’s leading fiber artists. Indigo—among the few blue dyes found in nature—is her magically rich and deep medium. The plant-derived color arrived in Japan in the eighth century and has been used ever since in table linens, clothing, and everyday objects, becoming an integral part of the country’s craft repertoire. Kyoto-based Fukumoto, who discovered indigo at 30, uses shibori, the ancient resist-dyeing technique, to produce abstract, conceptual works of textile art. Since the 1970s, she has been developing her voice as an artist connected to Japanese identity, one who is interested in culture, history, and the rediscovery of old or extinct textile production and processing methods. Her “canvases” are rare fabrics and vintage kimonos woven of linen and hemp, which she finds in tiny shops all over the country. Fukumoto deconstructs those old garments, immerses them in luminous indigo dyes, and then reconstructs them into remarkable wall tapestries that offer the viewer a quietly intense, almost mystical experience.

6. Kato Kosuke

Located an hour outside Tokyo, metal artist Kato Kosuke’s studio sits amid lush rice fields in rural Kanagawa Prefecture. Kato (b. 1988), who grew up in the area, has made it his life mission to reinvent and perfect Damascus steel, a long-lost medieval forging technique of Middle Eastern, not Japanese, origin. Once used primarily to make sword blades, the ancient process causes distinctive surface mottling reminiscent of the swirling patterns found in damask, the figured fabric also named for its close association with the Syrian capital. Rather than using it to forge weapons, however, Kato has adapted the labor-intensive, somewhat mysterious technique to create contemporary metal artworks: abstract, minimalist sculptures and objects distinguished by the subtle figuration of their skins. Kato enhances the intricate web of dapples, blotches, and striations—almost as ordered as a repeating design—by dipping the finished steel forms into an acid bath, resulting in works with the potent aura of archaic artifacts.

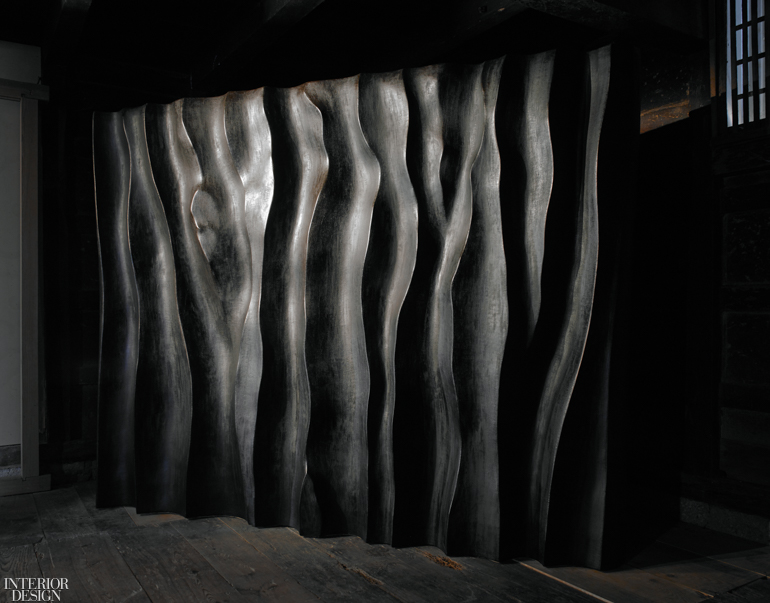

For thousands of years, Japanese artisans have coated bowls, boxes, and other utilitarian objects with layers of semitransparent urushi lacquer—a natural polymer distilled from tree sap—to give them lustrous surfaces with uncommon visual depth. Since the mid-90s, Tanaka Nobuyuki (b. 1959) has been at the forefront of a new generation of lacquer artists who are pushing the traditional medium in previously unimagined directions. Based in Ishikawa Prefecture, a region famed for its lacquerware, Tanaka creates fluid sculptural forms—rippling wall panels, freestanding monoliths, and undulating floor works, often monumental in scale—that put lacquer’s singular qualities to conceptually original ends. While adhering to the classic kanshitsu technique, a painstaking process in which multiple coats of urushi are applied to an intermediary layer of hemp, Tanaka uses polystyrene foam rather than wood to create his organic shapes. Pure and unadorned, the abstract sculptures’ rich-red or inky-black surfaces—alive with tactility, reflectivity, and translucency—are as mysteriously expressive as a Mark Rothko painting.

Read next: Fiber Artist Windy Chien in Conversation With Cindy Allen on Instagram Live