10 Questions With… Ishraq Zraikat

Ishraq Zraikat, a Jordanian textile artist based in the Hudson Valley in New York, has a life-long passion for making, designing, and research. A former practicing architect and fashion journalist, her design practice brings together all these skills and approaches in an idiosyncratic and tantalizing way. For several years, Zraikat has been focused on learning about centuries-old Bedouin loom-making and weaving techniques, and bringing them to life in performance pieces or architectural installations, for which she processes and develops her own wool materials. Recently she took part in “Arab Design Now,” one of the main exhibitions of Design Doha, a new biennale in Qatar created to showcase contemporary Arab art and design.

“I was very excited to work with Rana Beiruti (the cofounder of Amman Design Week and curator of Arab Design Now), because she has a unique perspective,” says Zraikat. “Being an architect herself, she is very interested in technique and story-telling, which is something that is at the core of my work. She’s also very focused on the ‘making’ process of any medium, as am I.”

Design Doha was the first time Zraikat had worked with wool in its natural color instead of dyeing it, something she found both challenging and exciting and now wants to pursue further.

Ishraq Zraikat On Her Love For Wool + Bedouin Weaving

Interior Design: How did your childhood contribute to your love of making and designing?

Ishraq Zraikat: My mother was very artistic and into crafting. She made clothes for my siblings and me, as well as objects such as painted silk cushions and ceramics for the house. I have six siblings and we spent a lot of time playing together and making our own toys, which kept us busy and creative. I used to build houses for Barbies/dolls, or make clothes for them from whatever materials I could find. At a young age, I learned that we could make a lot of things ourselves instead of buying them. When I was 13, my mother taught me how to trace patterns and use a sewing machine, so I became interested in fashion design and started collecting magazines and creating fashion scrap books of the images that inspired me. I feel blessed to have grown up before the internet and digital age when printed media was the main source of information and knowledge. My parents had a Childcraft Encyclopedia set in our library and my siblings and I spent a lot of time reading the books over and over. My favorite volumes were How We Get Things and Make And Do, which were all about how humans invent and make things. Now as a mother, I have bought the same exact set for my children.

ID: You studied architecture and worked in the field for a few years while developing your fashion skills. Could you share your journey from architecture via fashion to textile art?

IZ: I enjoyed working in the field of architecture, but early on I knew I wanted to design and make things with my own hands. While I was working as a junior architect in Amman, I continued to design and make clothes in my free time and developed a relationship with a local fashion magazine doing photo shoots and writing stories. I quit my job in late 2004 and worked on a collection of deconstructed vintage clothes, putting on a fashion show in a parking garage in downtown Amman. The reviews were positive, but I knew I needed to leave Amman if I wanted to become a real fashion designer.

I moved to New York City where I got two internships in the industry, one at Anna Sui and one at AsFour (now Kai Kühne), so I experienced the fashion industry at two opposite scales. A while later, I got hired to be a NY-based fashion editor for a Middle Eastern publication called Skin Magazine. As an editor, I started going to textile fairs and (thanks to my press pass) had access to exclusive events where I connected with professionals in the textile industry. It became clear to me that textiles was the medium in which I could combine all my past educational and professional experiences. After three years as a fashion journalist, I moved to Milan to pursue a masters degree in textiles and new materials design at the Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti (NAVA).

ID: What interests you most about textiles and fabrics?

IZ: I am most fascinated by the fact that designing a final product can start by creating the raw material itself. The potential for creativity is huge as I can go back in the production chain and inject my DNA as a designer at any stage of the production process. What’s more, every creative and technical decision that is made throughout the production chain has an impact on the finished product. By exploring different combinations of a number of variables, the possibilities are literally endless. I realize that a lot of the way I work goes back to when I was a child watching my mother make things from scratch and be resourceful and creative in her problem solving.

ID: You have worked with Bedouin communities in Jordan and used hand-made Bedouin looms in your projects. How did you get involved in that and what does it mean to you?

IZ: After being introduced to weaving in Italy during my master of textile design course, I began to wonder about the forms of weaving that are native to Jordan and the region. I found a couple of women in the village of Jabal Bani Hamida, in central Jordan, who still have traditional Bedouin weaving skills, and who graciously agreed to teach and share their knowledge with me. Our relationship immediately became a friendship based on a shared love for weaving and our Jordanian and Arab identity. By being in these women’s homes, seeing their day-to-day lives, and knowing their struggles as well as their victories, I understood what weaving meant to them. They are not just keeping an old craft alive, but still innovating and adding to it where possible. I started to value craftspeople differently as a result of meeting these women. By learning from them I was able to go from being a ‘designer’ to a ‘weaver.’

ID: You are very interested in native Jordanian wool. How is it different from other wools?

IZ: While learning Bedouin weaving, I realized that the weavers in Jordan use imported wool rather than local native wool. I started to ask why and the journey to answer the ‘why’ turned into my ongoing research into our native Awassi sheep wool. This wool is unique because this breed of sheep is quite pure and has been around for centuries. Its wool is strong and on the coarse side, so it is ideal for rug weaving, which is what the wool is famous for. Through my experience with processing the wool, I realized that it has potential for many other uses. I have since created an archive of wool samples that serve as a reference for material choice for my artworks. It is incredibly satisfying to be able to create my own raw materials based on the desired end use. Now, I happily call myself a ‘material developer’ as well as a textile artist.

ID: For Amman Design Week in 2019, you showed a piece that was part performance, part functional. Could you talk about it?

IZ: Creative Being at Amman Design Week 2019 was an homage to the creativity of the Bedouin people and the beauty of their weaving craft. It was an installation that transformed the Bedouin floor loom from a linear weaving instrument into a spatial structure that still functioned as a weaving tool. The metal frame was dressed with a closed circular warp that rotated around the frame as it was woven, creating an enclosure reminiscent of the Bedouin tent. The weaver sat inside the tent while weaving. It was a performance piece with a live weaving sessions throughout the week-long event. Bedouin weavers and I took turns weaving and interacting with visitors while answering questions. On the last day of the events, we completed weaving the full closed circular warp, took it off of the metal frame and demonstrated how the woven piece can be transformed into two small rugs. I wanted to show that the spatial structure was also a functioning weaving instrument that produced finished products.

ID: Do you keep close ties to Jordan professionally? What challenges do designers face there?

IZ: Yes, I always try to keep close ties to Jordan because it is my home and it is still also mostly ‘undiscovered’ creative territory with so much potential. It is very familiar yet still unknown to me, and the discoveries are always exciting because of its unique geographic location and culture that goes back millennia. I am inspired by designers and artists in Jordan who are often exploring the same cultural and historical themes that I am exploring in my work, but through different media. Although the ideas and feelings may be common, the material and physical expressions of each individual’s exploration becomes a revelation.

In my opinion, the biggest challenge for designers working in Jordan is getting raw materials. An artist or designer living and working in the US can go online and order pretty much any material or tool they need and have it delivered to their doorstep. In Jordan, ordering or importing anything for personal use, a studio, or a business is subject to high customs taxes and a lengthy approval process based on vague guidelines.

ID: What inspires you creatively where you are based?

IZ: I live in the Hudson Valley, which has an animal fiber agriculture scene alongside a thriving art and crafts scene. It has been very informative and inspiring for me to see an actual micro-economy right in my backyard where there are people who produce a raw material that is processed and used by end users in the same area. There are several fiber and textile initiatives that are doing amazing work in developing this micro-economy to better serve its beneficiaries, as well as promoting the locally produced fibers to designers and artists in New York City and nearby areas. It was here in the Hudson Valley that I first discovered the concept of craftspeople and artists producing their own raw materials.

ID: A few years ago, you produced a filmed performance piece in the Hudson Valley where you built and warped a loom. What was the inspiration for that piece?

IZ: The Nomadic Weaving performance I did during New York Textile Month in 2021 was something I had dreamed up years before when I started learning Bedouin Weaving in Jordan. During my very first weaving lesson, I arrived at my teacher’s house thinking she would have a loom set up for me, and I would just follow the motions and weave. Instead, there was nothing set up. We had tea and she took me outside to the back of her house where she began to construct the floor loom from found objects, one of which was a metal rod from a broken handrail outside her house. She was constructing the weaving tool itself before she began to teach me. By witnessing that, I began to understand the logic of weaving itself. The weaving instruments are arranged based on the desired end product.

That is when I understood that the nomadic Bedouins had developed their crafts and tools to accommodate their transient lifestyle. Since they traveled so much, their weaving tools needed to be things they could abandon and recreate again. They also needed to be able to move their loom mid-weaving without ruining the textile, and so that it can be rolled up, moved, then rolled out again in a different location where the weaving can resume. The free-spirit of the Bedouin floor loom captured my imagination. Going to the Hudson River banks and seeing the driftwood gave me the idea to try the concept there.

ID: What are your biggest challenges as a textile artist?

IZ: Controlling the influx of visuals I get through digital media. It can be stressful to see how incredibly fast our industry moves. There is constant pressure to put our work out there before it becomes ‘irrelevant.’ Although I do not believe that relevance should drive any artist, the media creates this pressure in the way it talks about art and design. When I limit my exposure to digital media, I feel much more focused and able to explore what I am genuinely interested in doing, as well as more in touch with my own creative identity. I still remember the pre-internet era when I used to buy magazines and sit with each issue for a month, looking at the same images over and over until the next issue came out. I was thinking and working at a much slower pace, my natural pace. The fast pace of digital media doesn’t allow us to sit with our ideas and thoughts long enough to see them through the entire process of what I call the ‘mode of design.’ We are quickly distracted by new stuff all the time.

read more

DesignWire

A Career In Color: Explore Olga De Amaral’s Retrospective In Miami

Explore a different perspective on color with textile artist’s Olga De Amaral’s retrospective at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami.

DesignWire

Cheers To 200 Years Of The National Academy Of Design

To mark its 200th anniversary, the National Academy of Design presents a showcase honoring contributions to contemporary American art and architecture.

DesignWire

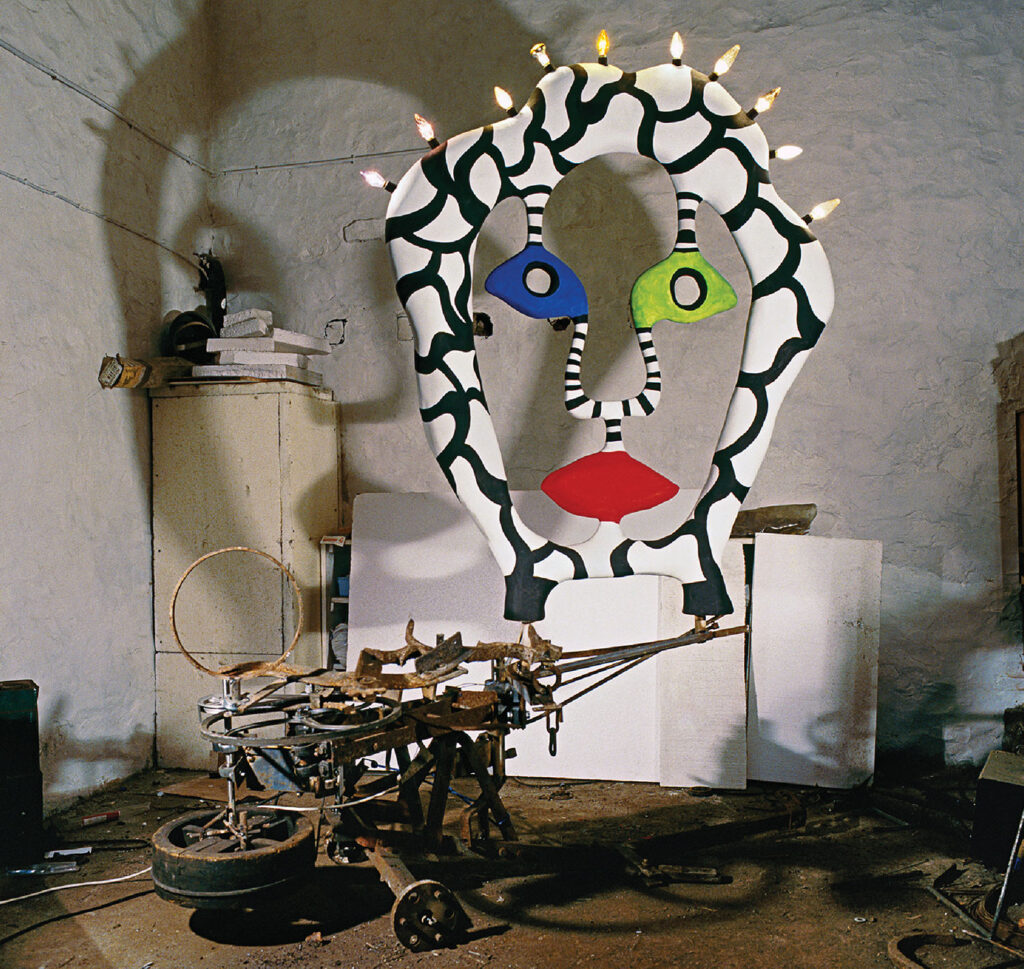

U.K. Exhibit Celebrates Unseen Works By Famous Art Duo

Peruse the exhibit dedicated to Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely at the Hauser & Wirth Somerset as part of the centenary celebration of Tinguely’s birth.