10 Questions With… Jan Ernst

Jan Ernst was a successful practicing architect in Cape Town, South Africa, when the Covid pandemic arrived. When his projects went on hold, Ernst began working with clay, developing a ceramics practice that imbued natural forms with almost supernatural, surreal qualities. His pieces quickly sold via Instagram and galleries came calling. In 2023, Ernst participated in the Objects With Narrative’s Postcards from Rotterdam group show and the Collectible exhibit in Brussels. Up next, he will show at Pitti Uomo in June as part of South Africa’s guest nation roster.

Here, Ernst talks with Interior Design from his new studio just outside of Cape Town, about how trees are architectural spaces for dreams, why he’s moving into plaster, and more.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jan Ernst Talks Surrealist Ceramics

Interior Design: When did you first become interested in design?

JE: I grew up on a farm for most of my life, in various parts of the country. So I spent a lot of time outdoors. Cape Town is a city with a lot of natural stuff around it. When I look at the stuff that inspired me, they were all super organic—whether it was spending time next to the beach looking at shells and coral or up in the mountains or in the forest. All of these natural things shaped the language in which I create.

ID: And those interests brought you to study architecture?

JE: I’ve always been interested in spatial design and spatial relationships, and how we respond to them and shape them. Architecture, in its purest form, is shaping a space and giving it character. How do we separate spaces, or match them? What is the character we want to give it, do we want it super simplistic, slightly more traditional? Is there a spiritual or emotional component? To me, those core ideas are so easy to translate into ceramics because it was about looking at the negative spaces around the object. When I create something, I can see it in someone’s living room or next to their bed. What do I want this object to make people feel? Do I want to make someone feel uneasy? Do I want to confront someone with a piece that is maybe, I don’t know, emotionally too evocative? Or do I want to create a quiet, serene experience?

ID: But you were trained as an architect?

JE: I have my master’s degree in architecture, and I worked as an architect for a couple of years. I did think: Did I waste six years of my life? I got a master’s degree and now I’m playing with mud! But in hindsight, all of these things are so intertwined—it’s just channeling them in a different way.

ID: How do you make someone uneasy with ceramics?

JE: My work is known to make people feel uncomfortable. Sometimes, I’ve been told that there are sexual references, which is not intentional at all but that always seems to surface in one way or the other. The pieces make them [question]: Oh, do I feel comfortable putting this in my living room? People see whatever they want to see.

ID: Was the architecture you were making similar to these ceramic forms?

JE: Maybe in the future I’ll have the opportunity to work in such an organic way in creating architecture. I think it’s extremely difficult to convince people to fall in love with these kinds of spaces. They are expensive to make because they’re not modular. But organic architectural spaces are under-explored. My architecture was vastly different. The only similarities were perhaps that they were super textural, super tactile, and there was a simplicity I can recognize in the ceramics now.

ID: What were your early ceramics like?

JE: I always wanted to create objects that had function and were usable. I thought: What’s the most simple thing I can try with a function that isn’t a mug or a bowl? To me, it was a candlestick. So the first things were candelabras inspired by the ocean. The way the light from the candles would interact with the ceramic pieces intrigued me very much, and that led me into lighting design. I started interrogating how I control light, and I started seeing light as a material and not the after effect of something being switched on. I was intrigued by how textures respond to the light. I also became equally interested in lamps without the lights switched on, because then you have these deep, dark recesses that kind of create mystery and intrigue.

ID: How did those investigations lead to larger pieces like the Day Dream Lamp?

JE: The Objects With Narratives gallery asked me to design a floor light, and I felt quite overwhelmed by the scale. I was walking around a forest, and I saw these trees that had been cut open. I looked at their annual rings and thought that we could use time and trees as a central theme in the work. During Covid, sometimes it felt like time was receding, or coming at us really quickly. I wanted to literally warp those annual rings and create deep spaces that would suck you in—like a vortex—but if you switch them on, they would illuminate and enlighten. I spent so much time trying to understand the canopy. As a boy, a tree was an architectural space I could climb into, where the world couldn’t touch me. So the canopy became almost a cloud or a dream you get lost in. I can stand under it and be enveloped entirely, and the base glows and gives off a warm feeling.

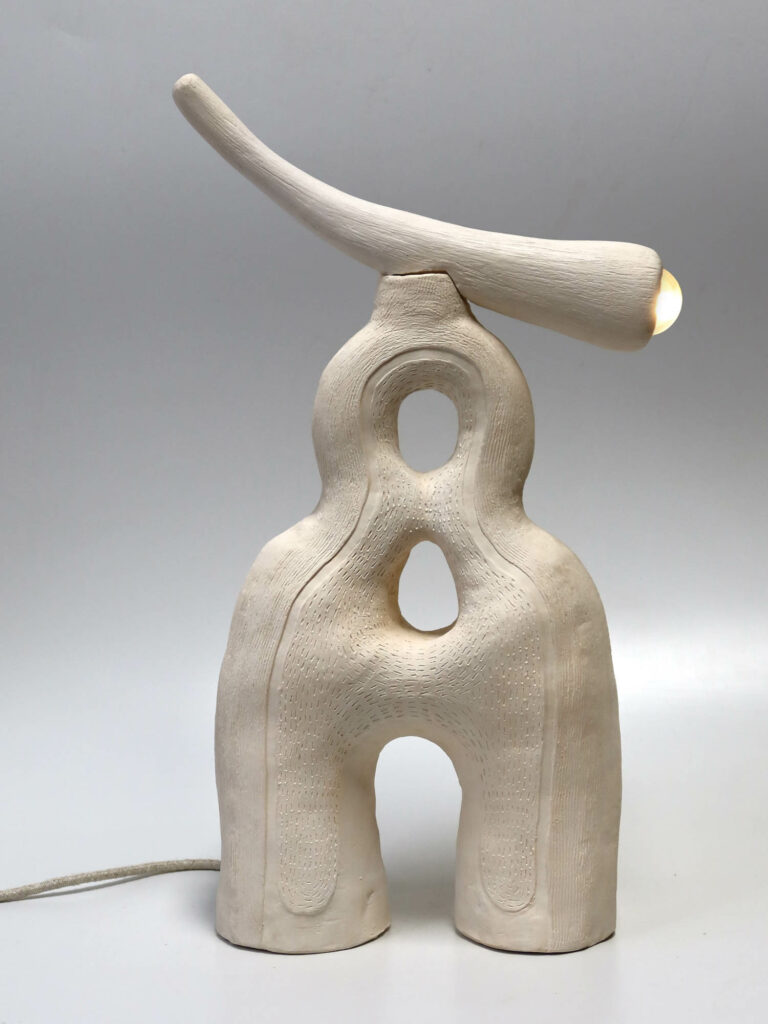

ID: What was the inspiration for the Flux collection?

JE: I was looking at copepods, which are microscopic little creatures that have very interesting shapes and forms. In general, they are super adaptable. So, for instance, you can take one that lives in salt water, in the ocean, and put it in freshwater, in the mountains, and it will adapt itself to the environment. So I wanted to explore that idea in the form of four sculptures with a lighting component. Shipping them from South Africa to Europe was a nightmare—the pieces had to disassemble and that became an extension of their aesthetic. The horn that sits on the arch can be taken out, and so can the mirror. You have to kind of put it together, so you as the end user become a part of the way the sculpture looks.

ID: You mentioned that people see human forms in your work—could you talk about how pieces like Twiggy and the Womb Lamp have been received?

JE: Twiggy has a built-out texture that we extrude and then puncture. It is a very confrontational piece and it makes people uncomfortable. It’s quite masculine, in a way, it demands attention. The Womb Lamp was inspired by a trip to the Cederberg mountains, about two and half hours from here. It’s an area of the country where some of the first human beings on this continent lived, and there are these incredibly beautiful caves that have different colors, like terracotta and ochre and white stone. They’re colors very much like the clay colors I use. The caves kind of hold you, and they demand that you think about where you are and what it represents. Not too far are some beautiful cave paintings. I saw the cave as a womb. The light component came from thinking about people making fires in these caves—it’s just symbolically representing that moment and celebrating their existence.

ID: Speaking of making fires, you’ve recently turned to a material that doesn’t require it. What interests you in making furniture from plaster?

JE: South Africa has a huge energy crisis at the moment, which makes it extremely difficult to fire ceramics as frequently as we would love to. Plaster has similar properties, in a sense, and I can achieve quite organic forms with it, but it doesn’t require electricity. It also allows you to scale up—you can make large forms with ceramics, but it becomes extremely heavy and fragile, so it doesn’t make a lot of sense to ship. There’s a robustness in plastic work. I’ve done a capsule collection of a stool, side table, a table and mirror, and a chair. I’m super excited to get going on it.

ID: What’s your new studio like?

JE: I had been working in a shared studio space, and it was fantastic to have other people around to bounce ideas off of and expand my knowledge. But I needed a bigger space, and the room to develop my own voice in my own studio. So we moved to Woodstock, a semi-industrial area not far from the city center. There are a lot of creatives working there, a lot of bronze and ceramic studios. And I’ve got two guys that work for me, much younger than I am, and we’ve developed a really beautiful relationship. Neither of them knew anything about ceramics or plasterwork when they started. I just said: We can figure this thing out together. It’s not like I’m a ceramic genius myself, but I’ve noticed a thing or two I would love to pass on. And so we’ve been learning a lot, and they’ve sort of become my ceramic hands when we’re under pressure.

ID: What’s next for you?

JE: We’re launching a new lighting collection at PAD Paris, and the plaster furniture at Galerie Philia in New York City later this year. I’ve been invited to Armenia to host a workshop in July. There are highlights in the year, and I just try to embrace them as they come. I have a vision, but I try to focus on two or three months at a time, because things just change so fast. I think that’s what I learned from Covid—not to get too excited about anything until it’s happening.

read more

DesignWire

11 Design Highlights from Collectible Brussels 2023

From a hot pink table sporting high-heel shoes to knitted coral-esque luminaires, here are 11 highlights from Collectible Brussels 2023.

Products

These Sustainable and Sculptural Pieces Made Waves at Alcova in Milan

See some of the highlights from this year’s Alcova, the showcase of group exhibitions in often overlooked locations around Milan.

DesignWire

14 Highlights from Collectible 2022

Creativity abounds at the 2022 edition of Collectible, a limited-edition design fair taking place May 20-22 in Brussels.

recent stories

DesignWire

Design Reads: A Closer Look at Jasper Morrison’s Work

Discover British designer Jasper Morrison’s wide range of furnishings, homes, and housewares in his cheeky retrospective “A Book of Things.”

DesignWire

Eco-Friendly Pavilions Take The Stage At A Chinese Music Festival

For a Chinese island music festival, Also Architects crafts reusable, modular pavilions that provided shade while resembling sound waves.

DesignWire

Meet The Production Designer For Wes Anderson’s New Film

Legendary production designer Adam Stockhausen shares how he crafted Wes Anderson’s The Phoenician Scheme’s cinematic world through spatial design.