10 Questions With… Koray Duman

For Koray Duman, cofounder of New York- and Istanbul-based architecture and design studio B-KD, starting a business seemed an inevitable career trajectory. Studying architecture in the late ‘90s in Turkey, Duman observed that his contemporaries often created their own practices with friends soon after graduation—an idea that remained firmly rooted in his mind, even after moving to the U.S. But it wasn’t until he moved to Manhattan following a job with Frederick Fisher and Partners in Los Angeles that Duman’s studio took shape as he began renovating the homes of friends. Today, he counts public spaces among some of his most meaningful projects, deeming them more necessary than ever as a means of bringing people together.

This year, Duman plans to complete two galleries in New York City as well as an artist’s home in Upstate New York. He also serves on the advisory boards of the American Society for Muslim Advancement and ProtoCinema and is an adjunct professor at Pratt Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Design. A former co-chair of the New Practice Committee at AIA NY, Duman stepped down to advocate for female leadership in the position. As for his own mentors, he counts structural engineer Nat Oppenheimer and architect Jeanne Gang among them. “They’re both so modest and gracious,” he shares. “We need more people like that who are generous and that’s something I’m very inspired by… we, as people, have to be generous to each other.”

Interior Design: Where did your interest in design begin?

Koray Duman: When I was in middle school, I was really interested in being a fashion designer. I am originally from Turkey. And I was very good at math at the same time, so there’s this misperception about architecture that if you are good at math, study architecture (laughs). So that was a suggestion to me: Maybe you should try architecture and once you study architecture, if you are still interested in other design careers then you can do your graduate studies in fashion design or something else. So that became my big interest in architecture through my interest in fashion design for me and once I did my undergrad I just continued on in architecture.

ID: Do you still harbor any fashion dreams?

KD: I do want to learn how to make and sew my own garments, but not yet. Unfortunately, in architecture we’re so removed from the end-product. Just the fact that fashion designers have an idea and they can put their hands on materials and build their designs by themselves is fascinating. The closest we can get to that as architects is making models of our designs. I love the idea that the final product is something you can produce in your own studios is something I still get very inspired by when I look at fashion designs.

ID: How did your architecture career begin?

KD: I did my undergrad in Turkey and moved to the United States for my graduate school at UCLA. During my time at UCLA, I interned for the architect Fred Fisher in Los Angeles. Then I ended up working there. His work has a lot to do with the art world and institutional projects, and he is also very close to well-known artists of his generation. I worked there for five years and I moved to New York. Similar to fashion design, I was also very interested in art and the way artists work with materials to produce their work. I located to the LES and started a great group of artists and young gallerists as friends and that led me to start my own office. I was helping them with some small projects and that was kind of like the beginning of the office.

ID: Have you always wanted to start your own business?

KD: The reality is, when I was going to undergrad in Turkey in the late ‘90s and during that time, if you’re studying architecture in Turkey and when you graduate if you want to practice architecture, there was no concept of a corporate firm or larger firms. The most common way of practicing is that you will just team up with a couple of friends and you will open your own office. That just stuck in my mind, that I’m studying architecture but at some point, I’ll have my own studio either by myself or with friends or colleagues. I didn’t question it even after coming to the U.S. I do remember when I was in school or working at Fred’s office, I was always on the side doing competition with friends. I did some residential renovations for friends on the side. I was doing that because I had this thing in my mind that as an architect, that’s where you will end up.

ID: What is it like to run a studio with a home base in two global cities?

KD: The borders between Turkey and the U.S. never closed the whole pandemic, but I only traveled twice. During the pandemic, we were working remotely so it didn’t matter where we were… it didn’t make a big difference. I have a small firm with a small staff. Before the pandemic, if someone told me we would be able to work remotely very easily, I wouldn’t have believed them. I think the pandemic forced everybody and now it’s working very well.

ID: As someone who designs hospitality and public spaces, how has the pandemic shifted the way you envision these?

KD: I realized that more than ever public spaces are much more important for us. Something that I realized and think about a lot is that, even before the pandemic, we were very isolated from each other as a society. The reason for that is that we were all in this digital world and in our own echo chambers, and I believe that is a big threat to our cities, our democracy, our future as humans. I became more and more an advocate of physical public spaces as a place where we can break out of our echo chambers and create dialogue between people. There is this urgent need for public spaces. When COVID-19 happened and then Black Lives Matter happened, that made me realize we are so disconnected and that it is even more urgent—creating an environment where people can have random meetings, talks, conversations when being with each other became much more important.

ID: You have a few gallery spaces that will be finished this year. Can you share a bit about those?

KD: Yes, we have two gallery projects. One in Chinatown and one TriBeCa that will open in spring. We did a very interesting feasibility on concept design for the public space of PS1 Museum that won’t open in 2022, it will take some time, but that’s something we’ll be working on this year. We are doing an artist’s studio and home for an artist, a ground up housing project, upstate that will be built in 2022.

ID: Where do you turn for inspiration?

KD: Biking. I bike every day in the city. Biking helps me a lot. Conversation also is something that’s very inspiring for me. My brain doesn’t think when I’m drawing, my brain thinks when I’m talking to people (laughs). That was difficult during COVID. We have an apartment that is almost like a salon for artists, writers, thinkers, and we always invite friends for dinner, it’s a place where we have a lot of creative conversations, which is always inspiring for me.

ID: As a design educator, can you speak to where design education is heading?

KD: I think we as architects think that if you are practicing, you always need to get commissions. So, if you structure your practice based on commissions, like the traditional way of doing architecture, I think the only way to practice that way is if you are close to power or in power. I think what is wanting in education now and what’s being talked about is: How can we educate students to be entrepreneurs, so they structure [their businesses] in a way that they don’t need commissions. I think that will make it more equitable and I hope that’s the way education will go is in that direction for our practice.

ID: Do you have a favorite piece of design in your home?

KD: We have two bathrooms, and both of them I built with 4×4 basic white Daltile ceramic tiles, which is very cheap, but we designed them in such a way that it creates a graphic that goes from the floor to the wall to the ceiling. It creates a special environment that doesn’t dictate you, but it kind of gives you energy. So I took a very common construction material, but the way it’s applied makes it something special and seeing how that inspires people is something I’d like to do more with my art and designs.

more

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Steve Leung and His Son, Nicholas

Interior Design sits down with the Leung family to learn more about their holiday home on Lamma Island and club in downtown Hong Kong.

DesignWire

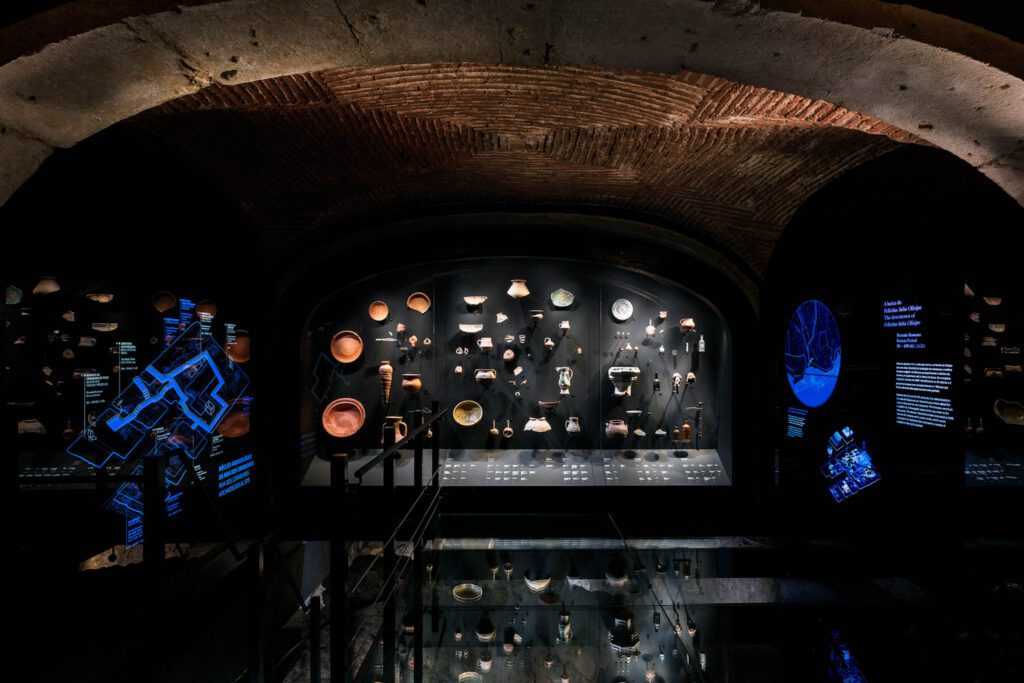

Atelier Brückner’s Lisbon Archaeological Museum Arrives

Want to brush up on your Visigoth artifacts? Stuttgart-based scenography experts Atelier Brückner has just made that easier with its innovatively immersive redesign of Archaeology in Lisbon: The Núcleo Arqueológico…

DesignWire

Interior Design’s Best of Year People Winners

See Interior Design’s 2021 Best of Year People winners.