10 Questions With… Ralph Giannone and Pina Petricone

Every level of STOCK T.C is buzzing as a long weekend wraps in midtown Toronto. On the ground floor, solo customers nurse cappuccinos in quiet bay windows. Families jostle with the evening’s meal or a hefty bag of double zero flour to attempt fresh fettuccine back home. On the second floor, servers weave through an open kitchen to a central bar and mustard colored banquets packed with hungry happy hour fans while the top floor transitions as brunch goers on the patio give way to patrons feasting on classic fare inside a glass pavilion.

It feels right that the 1930s Postal Station K—where those in North Toronto once received international packages—is now a showcase for produce and dishes from around the globe. Its backdrop comes courtesy of Toronto-based Giannone Petricone Associates.

Interior Design joins studio cofounders, husband and wife duo Ralph Giannone and Pina Petricone, in their new space in the city’s Spadina Avenue. They admit that late nights in Toronto’s Little Italy led to their first project, share their rationale behind revitalization of heritage buildings for contemporary purposes and muse on the future of hospitality post-pandemic.

Interior Design: How did two architects end up designing some of the Toronto’s hippest restaurant interiors?

Pina Petricone: Eugene Barone [the owner of Bar Italia, which Ralph often frequented] asked us to do his restaurant. We had just established our own studio. Bar Italia was an institution. But the landlord was raising Eugene’s rent, so he moved next door. At that time, neither of us had designed any hospitality or done any pure interiors before. We poured everything we had into that first project in 1995 and we fell in love with doing restaurants. It is so much faster than the institutional architecture both of us were doing. We got to test new ideas. And since we were already Bar Italia patrons, it was a perfect fit. Bar Italia was a mecca for ad agencies and the creative sector. We ended up getting referral work from them.

ID: And your decades-long relationship with Terroni founder Cosimo Mammoliti?

PP: Ralph and Cosimo are very close friends. He initially asked Ralph to help him get some permits. Then we ended up doing our first Terroni on Adelaide at the same time we designed the Los Angeles one.

Ralph Giannone: Terroni epitomizes Toronto. It’s joyous chaos. We create backdrops for theatrical dining experiences. Terroni parallels what we do with our urban design projects. Toronto, too, is an on-going experiment.

ID: Explain how STOCK T.C evolved out of Terroni and Cumbrae’s?

RG: Cumbrae’s is a third generation butcher big on zero waste. We designed its shop with a meat fridge fronting Bayview Avenue. That was also about theatre—and materials. How do we layer the glass to prevent condensation so people can see exactly the cut of meat they are buying?

PP: STOCK T.C is not a Terroni and not a Cumbrae’s—it is an offspring that became its own being. We had to abide by Ontario Heritage Act regulations and worked with heritage conservationists ERA Architects to get everything right. For example, we could not disturb the original façade and the glass pavilion we added to the roof of the original post office building could not be visible from the street. So we set it back and we ended up with a popular wrap around patio.

RG: The original coffered ceiling had all but disappeared. Our lighting design was a response to those missing coffers.

PP: We unleashed those coffers on the floor patterns as well. They are meant as ghosts of what was originally there. We used a layered approach for the architectural interiors to pull our intervention away from the host building, underscoring the legibility of where the historic building starts and stops.

ID: And The Royal Hotel in Picton?

PP: For heritage projects, it is about how to leverage the juicy bits to bring the entire building into its next life. It’s about layering a city with different eras and times, to build a living museum that cannot be replicated anywhere else. Our biggest challenge for heritage projects is scale. The Royal was formerly a Victorian mercantile building. Its bones are more domestic than what we expect in hotels today.

RG: Both The Royal and STOCK T.C are significant enough buildings that they should be incorporated into the urban fabric. Sometimes the new and the old programs don’t mesh. We often design heritage projects thinking whether a lay person will understand what we are trying to do. It’s a constant calibration.

ID: Now that we are emerging on the other side of the pandemic, what are your thoughts about food and the future of hospitality?

RG: The pandemic has really altered our communal experience towards food. It’s an on-going question—what will happen next? We see food retail and consumption happening more and more in the same space, like at STOCK T.C. It lets consumers be more connected to what they eat in a more intimate space.

PP: We see retail creeping into hospitality spaces. It is written into programs from the beginning, such as at Sud Forno on Temperance, which we designed for Terroni’s. And we are gaining confidence with designing them since we get involved at the concept stage.

ID: Ralph, how did you end up owning a hotel in Italy?

RG: My parents are from the same town in southern Italy. My father’s entire family is still there. When we used to visit, there was no place to stay. We found a fortified estate with turrets to guard against invaders. My brother and I purchased and renovated it along with my dad, who was a builder. It took four years to get it up and running. It’s a gentle invasion of a heritage property that tourists can easily understand. And, as Canadians, we had to have a fire pit to roast s’mores.

PP: We changed it to a white exterior to be more consistent with the area’s hill towns. We also carved out a swimming pool.

ID: After so many hospitality projects, do you consider yourselves hospitality specialists?

PP: We see ourselves as architects that work at the extremities of the profession. It is not about typologies.

RG: We see ourselves as custom tailors. We do bespoke projects and we are personally interested in the final product.

ID: Pina, why teach architecture at The University of Toronto?

PP: I loved school and went back for my master’s degree at Princeton when Ralph was working at Teeple. Then, when we started our studio, we knew that we needed a steady source of income before we got enough clients to sustain the business. I was offered a chance to teach at our undergrad alma mater. I fell in love with teaching and have been teaching at University of Toronto ever since. At the moment, my teaching commitment takes up about 50% of my time. With our house project near the escarpment, my teaching duties at the Daniels Building and our studio here, my entire life revolves around Spadina Avenue!

ID: You are finishing your house this fall, right?

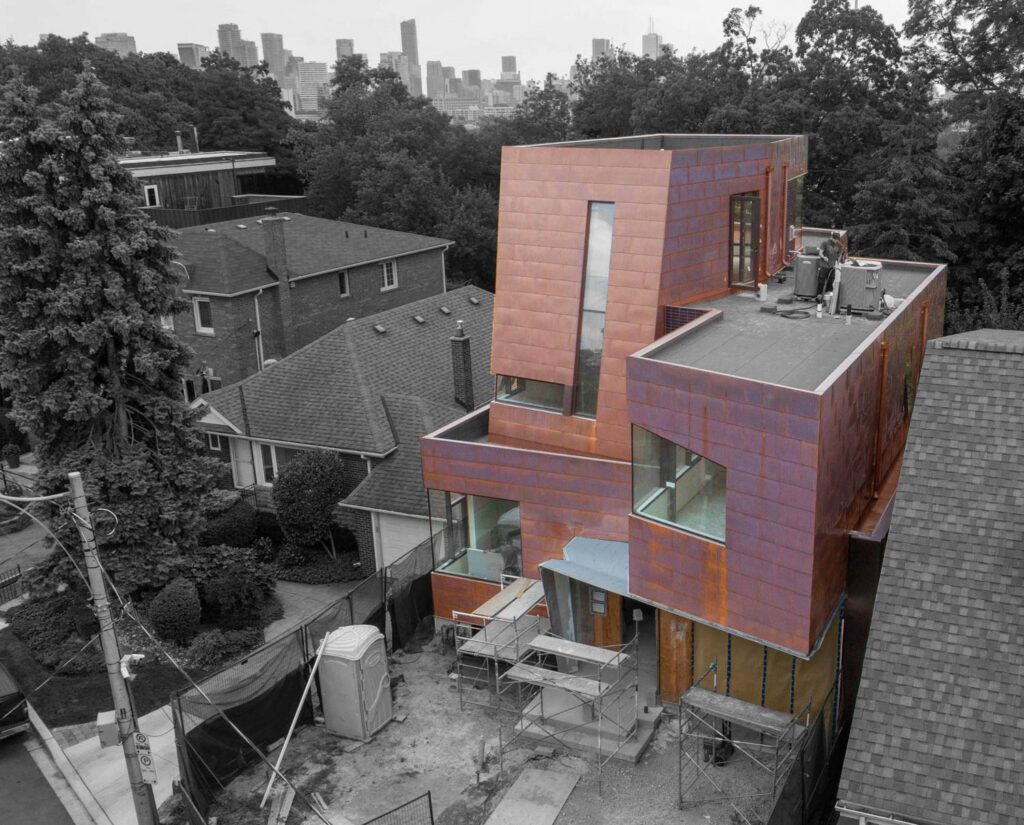

PP: Yes, finally! We bought the house back in 2003 and were all set to renovate when I found myself pregnant with Luca, our youngest. We then put our plans on hold and began working on it again several years ago. We wrapped the exterior with copper to pull and push spaces, sliding them from back to front. It looks like an orange peel that allows us to pull away from our neighbors, too. We should be finished by October.

RG: It was tough during COVID. We were so busy. We had no time to work on it.

PP: A by-product of COVID is that our older sons, Gianlorenzo and Massimo, became part of the project. Both are studying architecture at UofT—Gianlorenzo is doing his master and Massimo is an undergrad. During COVID, with everyone stuck at home, Gianlorenzo worked on the house doing construction, renderings and millwork. He learned so much. The entire experience brought us closer.

RG: Gianlorenzo was our site super! Massimo helped, too. They are passionate about the project.

ID: Your thoughts about Gianlorenzo and Massimo also being architects?

RG: When each told us that he wanted to study architecture, I was not happy. Are they crazy? Can’t they see that all their parents do is work? I told them to get a management or law degree instead. But then I have to admit that there is nothing better to study than architecture—we both loved it. We are on this path because of it. We don’t know if they will actually be architects. It will be interesting to see what they do with their degrees.

PP: Every parent wants her kid’s life to be easier. Our sons are smart and talented. We support whatever they want to do.

read more

Projects

Moinard Bétaille Polishes Up the Hotel Cala di Volpe in Sardinia

In the Mediterranean, Moinard Bétaille polishes up the Hotel Cala di Volpe, an Italian screen legend on Sardinia.

Projects

Studio Astolfi Takes Inspiration from the Seaside Town of Cascais, Portugal for This Restaurant

Studio Astolfi transforms a former restaurant into an intimate, homey oasis for Chef José Avillez’s Cantinho do Avillez.

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Tiffany Howell

The multi-talented Tiffany Howell talks with Interior Design about her studio Night Palm, launched in 2016 along with William Melton.

recent stories

DesignWire

Design Reads: A Closer Look at Jasper Morrison’s Work

Discover British designer Jasper Morrison’s wide range of furnishings, homes, and housewares in his cheeky retrospective “A Book of Things.”

DesignWire

Eco-Friendly Pavilions Take The Stage At A Chinese Music Festival

For a Chinese island music festival, Also Architects crafts reusable, modular pavilions that provided shade while resembling sound waves.

DesignWire

Meet The Production Designer For Wes Anderson’s New Film

Legendary production designer Adam Stockhausen shares how he crafted Wes Anderson’s The Phoenician Scheme’s cinematic world through spatial design.