How This Emancipation Exhibit Came To Life—And Where It’s Going Next

What does Black freedom mean today? An exhibition at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, titled “Emancipation: The Unfinished Project of Liberation,” offers fresh insights into the question with works by seven Black artists.

John Quincy Adams Ward’s sculpture The Freedman, part of the museum’s permanent collection, serves as a starting point for the show, which marks the 160th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. “Emancipation is a verb-to-be. It’s an ongoing process,” offers participating artist Letitia Huckaby. “As the title of the show declares, it is an ‘unfinished process.'”

On view through July 9 in Fort Worth, Texas, home of the National Juneteenth Museum, the exhibition has even garnered the attention of an extra special visitor: Opal Lee. Known as the grandmother of Juneteenth, Lee played a pivotal role in commemorating the order given on June 19, 1865 to emancipate those who were enslaved, advocating for the date to be a federally recognized holiday by walking from Fort Worth to Washington, D.C.

“What excites me the most about being in this exhibition is having the opportunity to re-contextualize the meaning of ’emancipation’ alongside such talented artists,” said Alfred Conteh, whose work is on display. “I’ve been in many group shows over the years, but very few where Black artists are centered to redefine what the construct of freedom means to us and our people.”

The exhibition was curated by Maggie Adler, a curator at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, and Maurita Poole, executive director of the Newcomb Art Museum, Tulane University. The two also had input from Horace D. Ballard, curator of American Art at the Harvard Art Museums, as well as the creatives themselves.

While the majority of artists involved identify as American, Jeffrey Meris, who was born in Haiti and grew up in the Bahamas, offers a fresh dialogue on the role of place. “The older I get, the more I question the value of nativity or nascence,” Meris says. “As a person of the African Diaspora, unfortunately I don’t have the privilege of saying: ‘This doesn’t pertain to me because I’m not African American.’ I still get read and understood through that very specific lens.”

Here, Adler and Poole share insights into the nuances of selected works, the making of the exhibition, and where it’s heading next.

An Interview With Exhibition Curators, Maggie Adler and Maurita Poole

Interior Design: Where did the idea for this exhibition originate?

Maggie Adler: Our now retired head of facilities, Alfred Walker, started at the museum when he was 18. He’d been at the Amon Carter Museum for 42 years, and he’s from Fort Worth’s all Black neighborhood. [For the museum’s 60th anniversary,] we had asked non-curators to write labels for the work of their choosing, and he chose The Freedman. He wrote that even though this person has broken his own shackles, the shackles are still there and present in the 21st century. We’ve come a long way as a nation, but how far have we not gone? And that was the inspiration. I had been thinking of doing something with The Freedman for a while, but when Alfred said “the shackles are still there,” I was like: Okay, we’re doing this show.

ID: How did you select artists for the show?

MA: We were all interested in not repeating the same artists who stand for Blackness in America—we love those artists—but people keep going to same well, so it was very important for us to select up-and-coming or mid-career artists. Because Maurita and I are both located in the South, it was also important to us to have a connection to the American South and that experience.

A lot of shows about the Civil War or contemporary reactions to enslavement rely on photography, and because we were starting with a sculpture, we wanted artists who were comfortable with installation or more sculptural work. Letitia Huckaby is someone I’ve worked with briefly and who I’ve always wanted to work with—to have a hometown Fort Worth artist in the mix was exciting. Hugh Hayden was born in Texas, and I’ve worked with him previously. Maurita has been close with Alfred Conte, having been director of Clark Atlanta University, which is where he calls home. We snuck in Jeffrey Meris. We are a museum of artists from the United States, but increasingly that definition is expanding. Even though Jeffrey isn’t technically from the U.S., he lives and works in New York. Maya Freelon we picked because we wanted a degree of hope and levity, whose work lends itself to a discussion of freedom and liberation or lack thereof. Sable Elyse Smith and her relationship to the carceral system—that was also really important.

Maurita Poole: Most artists were already part of the show when I came on board, selected through Maggie and Horace, except Alfred Conteh from Georgia, my home state. I really wanted to include him as an extraordinary person, painter, draftsman, and sculptor. His works are powerful pieces; they contemplate systems of inequality on Black bodies in sculpture and paintings. I felt we needed this addition to the show to spark debates we don’t usually have and to have a different lens as an artist from Georgia—from the South—who is deeply committed to having these conversations in the Southern context.

ID: What do you mean by having these conversations in a ‘Southern context’?

MP: In the American South, some of the distance to slavery is not there. We do have distance in terms of time and histories of slavery, but the South is implicated immediately in that context. The reality is, if you think Civil War, you think: Southern war, secession, slavery. To have someone like Alfred who has grown up in the South, remains in the South, and whose work deals with aftereffects of slavery and systems of oppression in the American South in the 21st century is really powerful.

ID: The exhibition is ongoing during Juneteenth; how do you feel the works continue the dialogue about emancipation?

MP: We’re trying to produce a nuanced perspective on emancipation. What I love about Juneteenth is that it’s a celebration about the fact that there were some strides made—for me that’s critical. It’s a little medal we can celebrate. We haven’t resolved the problems of inequality, but we do not have slavery as it existed in the 19th century. We can look at where we were, and look at the problems that still exist, and look at what’s possible. Change is not possible if we don’t look at what was and what is happening now, and we have some of the best artists in the U.S. giving us their perspective about this issue.

ID: What’s next for this exhibition?

MA: I’m looking forward to the fact that the tour has three stops in the American South and then a foray to Williamstown, Massachusetts. The benefit of the other venues is that they’re all academic art museums or connected to universities, so you never know what seeing this kind of representation does for the next generation of artists and curators—to know that there’s room for them, especially in a historical American collection. [Two of Sadie Barnette’s drawings will join the Amon Carter Museum of American Art permanent collection, Adler adds.]

MP: I’m enthusiastic that the show is coming to New Orleans. In the context of each region, the interpretation is going to be more nuanced and mixed. The audiences coming to see the show here will be coming from mostly Louisiana, maybe a few from Mississippi. In each context people will have different perspectives about how we read this time period and how we read this contemporary moment. There are different Souths. It will be fascinating to get responses from our publics about the show and see what draws them in the most.

read more

DesignWire

7 Black Artists Offer a Dialogue on Freedom in This Exhibition in Fort Worth, Texas

An exhibition seeks a nuanced understanding of what freedom and agency look like for Black Americans in 2023.

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Shawnasia Black

Shawnasia Black, co-chair of the IIDA New York Equity Council and a designer, shares insights into shaping a more inclusive and equitable industry.

DesignWire

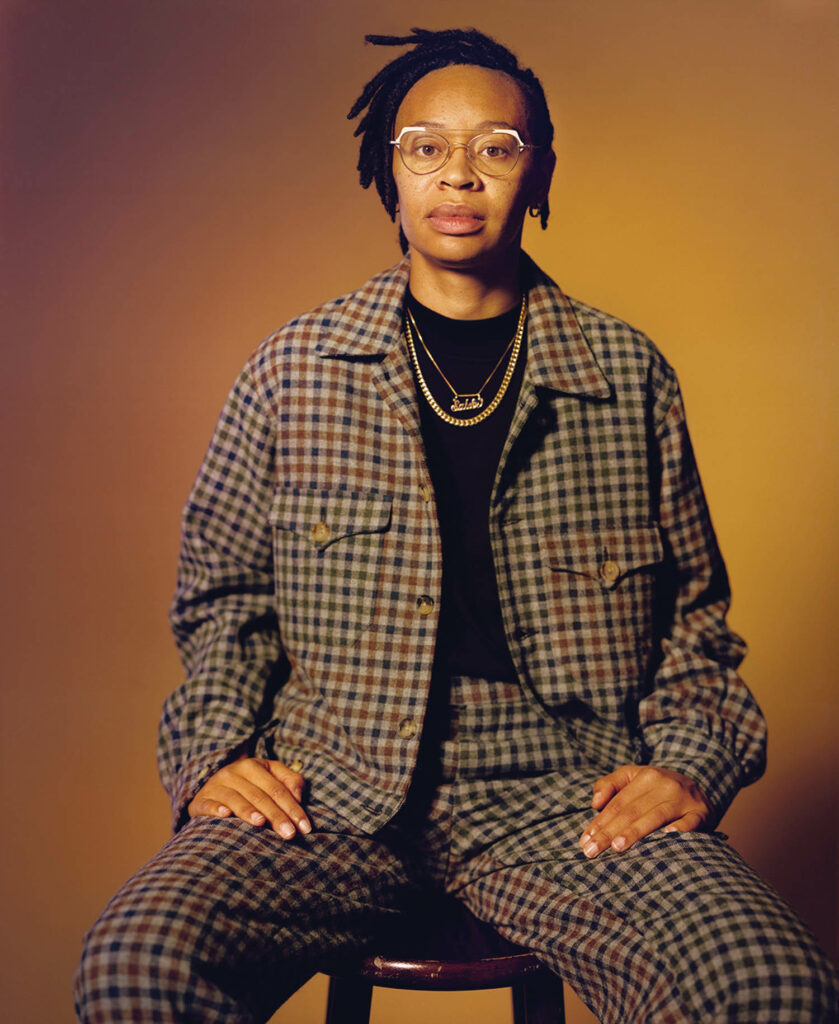

10 Questions With… Thabisa Mjo

Thabisa Mjo works with local artisans to craft and embed South African stories into her brand’s light collections, ceramics, and furniture.

recent stories

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Damon Liss

Tribeca interior designer Damon Liss blends warmth and timeless flair with collectible vintage pieces to create thoughtful residential spaces.

DesignWire

Design Reads: A Closer Look at Jasper Morrison’s Work

Discover British designer Jasper Morrison’s wide range of furnishings, homes, and housewares in his cheeky retrospective “A Book of Things.”

DesignWire

Eco-Friendly Pavilions Take The Stage At A Chinese Music Festival

For a Chinese island music festival, Also Architects crafts reusable, modular pavilions that provided shade while resembling sound waves.