An Oscar Niemeyer Building Brings a Brazilian Lilt to Paris

In 1967, Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer left his homeland for what would become almost two decades of self-imposed exile in France. Three years earlier, an American-backed military coup had overthrown Brazil’s government. Despite being renowned for designing the main buildings in Brasília—the spectacularly modern inland capital planned and built from scratch in a gobsmacking three and a half years—Niemeyer, who had been a member of the Brazilian Communist Party since 1945, found his work dried up under the implacably hostile right-wing dictatorship. So the displaced architect, who was twice refused entry to the U.S. because of his party affiliation, set up shop on the Champs-Élysées in Paris.

One of Niemeyer’s first major commissions there was a new Paris headquarters for the French Communist Party, powerful enough at the time to win more than 20 percent of the national vote, though its fiercely pro-Soviet ideology would become increasingly unpopular and out of touch. The architect had abandoned his country but not his lifelong political principles: In a show of solidarity, Niemeyer worked on the project for free. But his Marxist-Leninist sympathies were not limitless. “On the politics, I’m with you,” he told a Moscow audience in 1963. “But your architecture is awful.” The French Communists would get one of the least-Stalinist buildings imaginable.

Oscar Niemeyer’s Paris Commission Reflects His Signature Aesthetic

By the time he died in 2012, a few days before his 105th birthday, Niemeyer was generally regarded as the last of the 20th century’s great modernist masters—a protean talent who, at his best, was as innovative and inventive an architect as any of his distinguished peers. From the beginning of his career in the ’30s, working with Le Corbusier in Rio de Janeiro on the Ministry of Education and Health headquarters—Brazil’s first modernist building—Niemeyer’s cast-concrete structures infused the hard-edged, flat-planed International Style with his love of undulating lines and voluptuous forms. “I am attracted to free-flowing, sensual curves,” he wrote in his memoirs. “The curves that I find in the mountains of my country, in the sinuousness of its rivers, in the waves of the ocean, and on the body of the beloved woman.”

A Behind-the-Scenes Look at the French Communist Party Headquarters

No wonder, then, that Niemeyer’s early biomorphic work, with its swelling shapes and fluid contours, is almost always compared to the samba, the sensuous dance-rhythm that embodies Brazil’s nonchalantly eroticized culture. But by the late ’50s, when he designed Brasília’s elegantly charismatic buildings, the architect’s style was closer in feel to the newly minted bossa nova: cooler, jazzier, more cadenced. It is this urbane, smoothly syncopated quality that pervades the complex Niemeyer devised for the French Communists. Unlike the Brazilian capital, however, the headquarters, located in northeast Paris’s appropriately working-class 19th arrondisement, were not built overnight. Although the main building was inaugurated in 1971, for economic reasons the scheme’s most spectacular element—a mostly underground auditorium for meetings of the party’s Central Committee—was not completed until 1980.

Niemeyer went to great pains to preserve the openness of the sloping corner site, which faces the leafy oval of the Place du Colonel Fabien. He housed the party’s administrative offices in an undulating six-story slab set high on the hillock, well back from the street. Sheathed in a stainless-steel and tinted-glass curtain wall designed by Jean Prouvé, the sinuous building sits on short concrete piers so that it appears to float above the broad paved forecourt, which swells upward to almost meet it. The main entrance, under a wavy concrete canopy, is surprisingly discreet: a slotlike aperture that leads down to a vast subterranean lobby. Principal access to the offices above is via a separate circulation tower tucked immediately behind the building.

Niemeyer’s Biomorphic Forms Breathe Life into the Structure Inside and Out

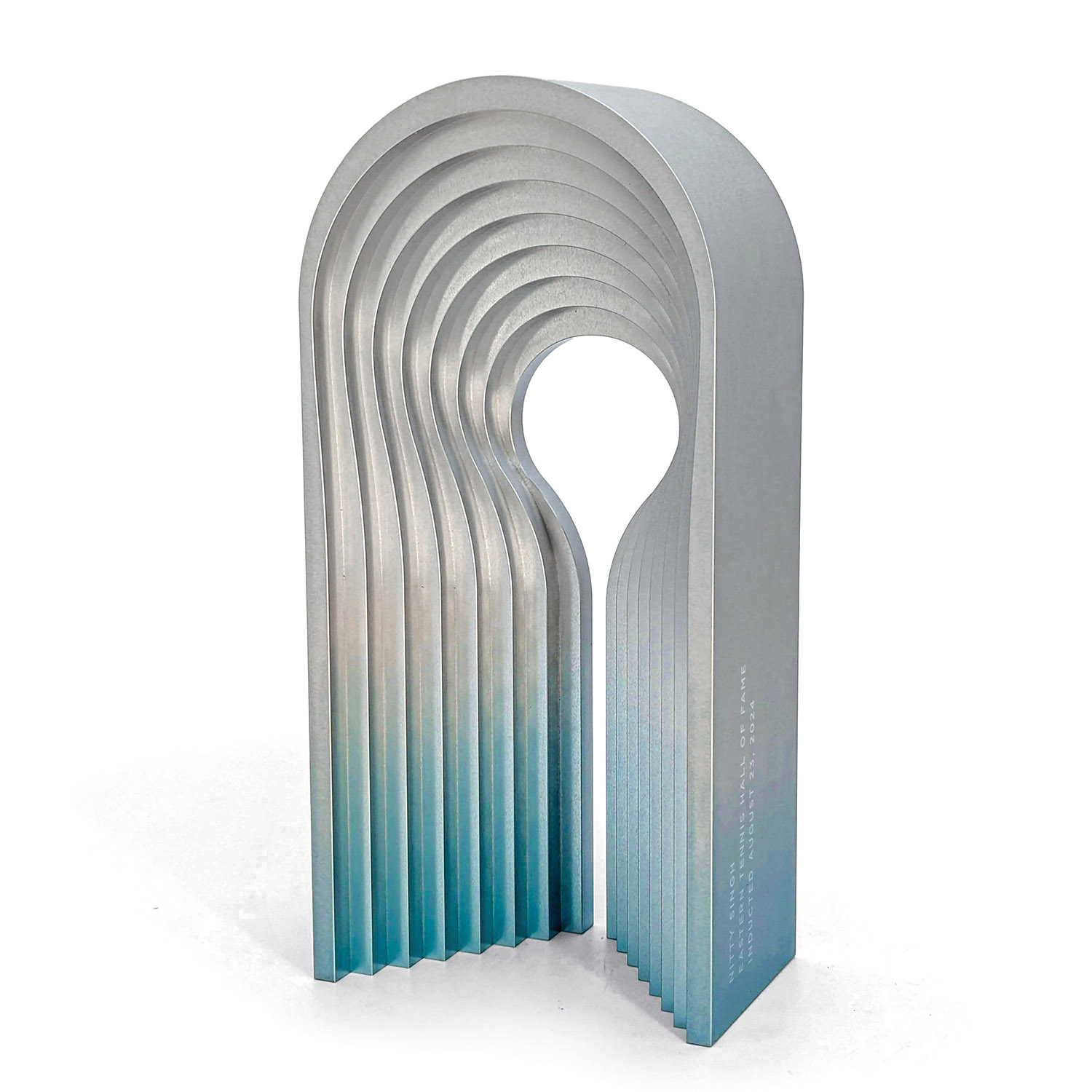

The only interruption to the plaza in front of the secretariat is a smooth white concrete dome that rises mysteriously out of the earth like some space-age burial mound. It is, in fact, the top of the bunkered auditorium— a dazzling 450-seat circular chamber that’s like a smaller, more futuristic version of the General Assembly Hall at the United Nations in New York, another headquarters that Niemeyer and Le Corbusier worked on. The interior of the 36-foot-high cupola is hung with several thousand white anodized-aluminum strips, which turn the entire ceiling into a glowing nebula of diffused light. Beneath it, curving rows of delegate seating face a low platform stage defined by a sweeping white concrete canopy that echoes the one over the main entry.

Set into the auditorium’s sloping walls, airlock-style sliding doors open onto the lobby and its adjoining subterranean facilities. These include lounges, an exhibition area, a bookshop, circular sunken courtyard, and, spread across three lower basement levels, various conference rooms (including a leaf-shape one for meeting foreign delegations), a cafeteria, and TV studio. Sleek curves abound, but the cast-concrete walls and other architectural elements bear the texture of the boards that formed them, giving the interiors an attractively handmade quality that saves them from looking too slick or movie-ready.

That hasn’t stopped the complex from becoming a favorite location for art directors and fashion designers who have staged unapologetically capitalistic photo shoots and couture shows in and around it. Niemeyer was certainly aware that his building, which has been a listed monument since 2007, could serve such bourgeois ends. “Architecture does not change anything,” he said more than once. “It’s always on the side of the wealthy.” The important thing was to believe that beautiful buildings make life better for everyone, something even Georges Pompidou, the right-wing French president at the time, seemed to acknowledge when he said that Niemeyer’s coolly sensual landmark “was the only good thing those Commies have ever done.”

Keep scrolling to view more images of the project >