10 Questions With… Jane Withers

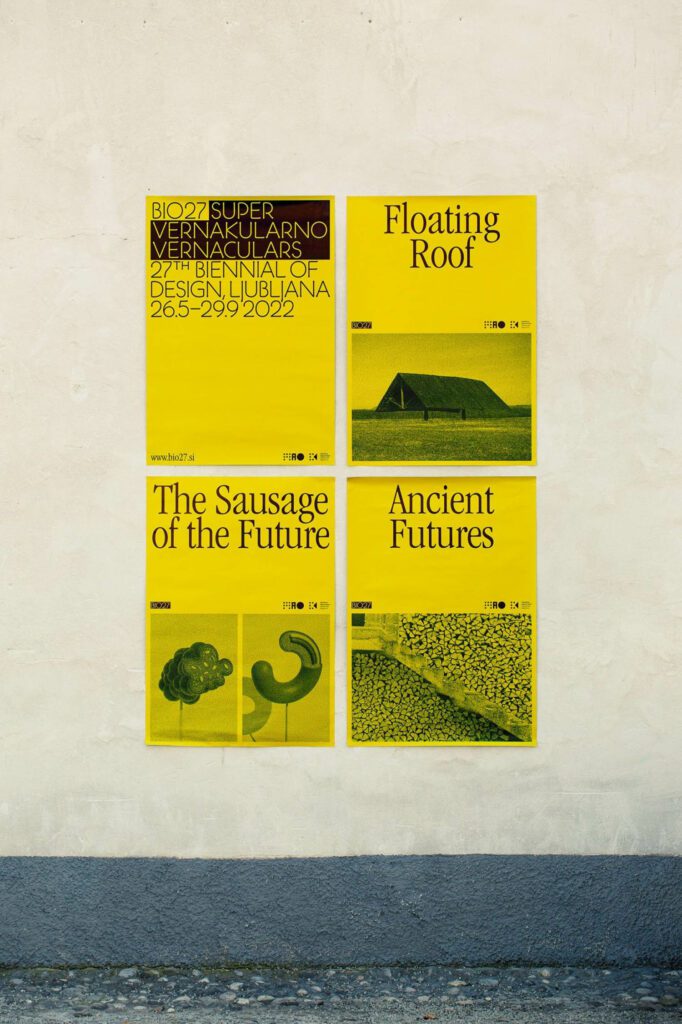

The 27th edition of BIO Ljubljana (BIO27), the oldest design biennial in the world, opens May 26 under the curatorship of Jane Withers. Exploring the theme “Super Vernaculars – Design for a Regenerative Future,” it will feature forward-thinking and environmentally-conscious designers, architects, and thinkers with a focus on how we can build a more resilient and equitable future.

Withers is a leading design curator, writer and consultant based in London. Her studio works on curation, programming and design-led strategies to address social, cultural, and environmental challenges. Regarding her approach to the Biennial, she says: “A lot of the projects are things we’ve been working on for a long time because we want to show that things are happening. That’s the challenge. Design is often very good at throwing up great ideas, but the tough bit is making them happen and driving them through to reality. The time for thinking and raising awareness is gone, we now have to shift to action. So this biennale has a very different tone to what one might have done a few years ago.”

Interior Design: How did you first hear about BIO and how is it different from other biennales?

Jane Withers: I had heard about it for some time, especially the recent editions curated by Jan Boelen, Angela Rui and Maya Vardan and Thomas Geisler, which seemed to tackle very interesting subjects in some depth and engage with topical issues as well as with the host country. Design biennales with an experimental focus, which generate new work and discussions are quite rare but BIO is very embedded in the local design and architecture scene and people, also in institutions outside the design world keen to collaborate. There’s a very inspiring, open attitude.

ID: How did you come up with the theme and title “Super Vernaculars” and what does it mean?

JW: “Super Vernaculars” is an attitude I’ve been observing for quite a few years where designers are exploring practices rooted in vernacular traditions, systems, and cultures and seeking alternative and innovative narratives for the 21st century. These practices often look to nature for inspiration and use nature-based non-extractive materials. Reviving traditional practices is in no way about nostalgia or looking backwards, it’s about saying that often there are very valid and common sense responses and ways of doing things that were rooted in climate, weather and terrain and developed for generations that have been lost in our capital-centric, industrial-centric recent era. It’s a very topical subject but this attitude isn’t going to grow without interrogation, discussion, and empowerment. So how can we grow and nurture this approach? How can we power it and empower it given that our current systems are so entrenched?

ID: Can you give me some examples of ancient practices that are being revived and some of the designers or studios that feature in your main exhibition?

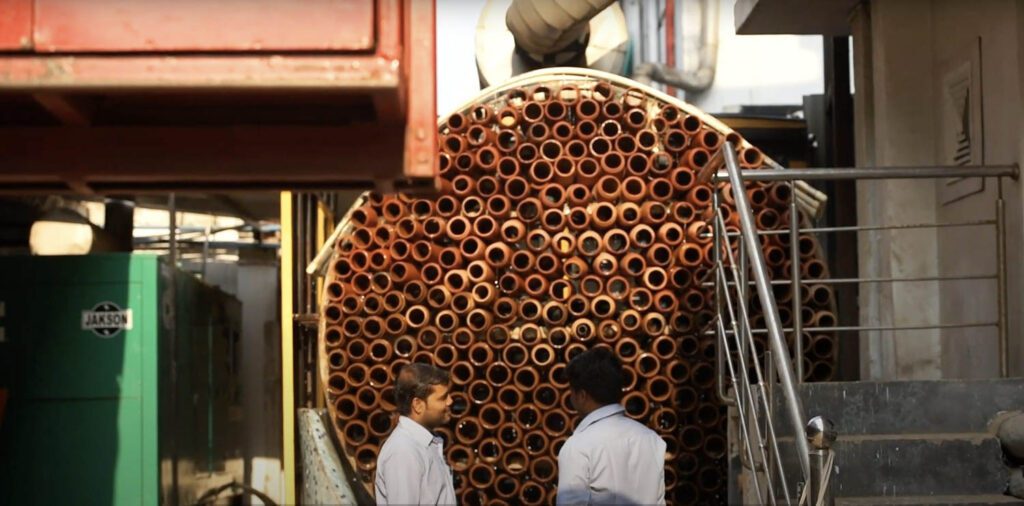

JW: We have included Ant Studio from Delhi, which is currently looking at ancient practices for cooling buildings through Jaali screens and evaporation as alternatives to environmentally costly air conditioning. It’s crazy that we build glass buildings, and then have to cool them down. You will also see some of the new materials research by Atelier LUMA in Arles and a project by Ooze Architects in Chennai. Chennai has faced a drastic water crisis over the last few years, and they’ve shifted thinking to explore alternative nature-based systems. Ooze Architects is now trialing a project there where they’re restoring the existing temple tanks and step wells in a historic area, as well as installing new tanks, and linking them with bio-swales and ponds to clean water, effectively bringing back an ancient vernacular that has been re-engineered for the 21st century. A few years ago you wouldn’t have thought it possible the city would take this up, but the scale of the crisis is making them try different ideas. That’s just a few of the things we present.

ID: There’s also an introductory section to the main exhibition about forgotten vernaculars. What can you tell me about that?

JW: It’s a snapshot of the ideas informing the Biennale. So there’s Bernard Rudofsky who in the 60s opened up this world of vernacular with his book Architecture Without Architects. But we also have a section created by the Triennale in Milan looking at how Enzo Mari and his 1970s manual Autoprogettazzione was essentially a vernacular, providing open source plans to people, teaching people to make things themselves. We have three of the 200-plus prototypes Riccardo Dalisi made of a Neapolitan coffee maker in the 70s that was eventually produced by Alessi in 1987. The idea is that vernaculars that have often been ignored in the 20th century and slightly written out of the mainstream of history are actually embedded in the culture and more alive than we’ve often imagined.

ID: Tell me about some of the commissioned projects in the Biennale? There is a production platform featuring Slovenian inter-disciplinary teams and mentored by international artist designers that will tackle compelling local problems, is that right?

JW: BIO is unique in that the last few editions have engaged with a production platform. Previously these were quite international in focus, but because of COVID and the nature of this biennale, we thought it would be a more interesting, more relevant, and a more responsible approach to help grow the local design ecosystem. So we did an open call and brought together international mentors with local inter-disciplinary design teams for five commissions. The teams have had about six months to develop their ideas and it’s interesting how far you can get in a short time with good people. I hope this will embed the approach in the region so it’s not just another biennale on the circuit that rolls into town, creates waste and moves on. I think that age is over. You have to think of how you direct resources responsibly, how you grow long term, what the legacy and impact is.

ID: On that note, one of the production platform commissions is the development of an open source toolkit to help design teams at BIO and future design events reduce the impact of their work. Tell me more.

JW: We realized we wanted to embed a regenerative approach throughout the entire event but how do you do that? One option is that you hire very expensive consultants and they tell you the footprint of your past biennale and so on but to me it’s more of a mindset than a bean-counting issue. It’s about how we understand best practice and how we share information. So many designers who work in exhibitions are keen to do this, but don’t really know how. So we designed a brief with local design team Futuring (who are being mentored by sustainability expert Sophie Thomas) who are undertaking an environmental audit of the Biennial, seeking to reduce its impact and looked at building a series of guidelines that will be shared open source as part of their production platform. So one of the legacies of the Biennale will be this very accessible toolkit that can help guide designers with very practical info about what questions to ask, what the pitfalls and problems are, what to do about shipping and packing. I think vernaculars are about sharing knowledge and growing it. So it’s getting back to that really. And on that note the catalogue will come out at the end of the biennale too, because we want to capture a lot of the production platforms’ work in it and create a sort of manual to the approach going forward. It will be made out of paper waste and stitched without glues so that it can be disassembled.

ID: What specific Slovenian vernaculars did you explore?

JW: There’s a wonderful architect called Jože Plečnik who is one of the city’s main architects and worked mostly between the two world wars. Several of his buildings were put on the UNESCO World Heritage List last year. He is almost like a poster boy for Super Vernacular because he reused materials, adapted things and was amazingly resourceful. There was a show of his work in the 80s at Centre Pompidou but I think he’s really being rediscovered again now. We have turned an existing little Pleznik kiosk, an adorable little temple really, into an exhibit and info point from which tours of his work will depart. We also commissioned Czech architectural historian Adam Štěch, who is also one of the production platform project mentors, to documentvernacular and regional modernism in Slovenia and Croatia in a new series of photographs. It’s called ‘When International Style Went Local – Vernacular Modernism in Croatia and Slovenia’. I think people will be really surprised how materials have been adapted to the local context. You will see the work of a wonderful Slovenian architect called Oton Jugovec who did a floating roof, an archaeological shelter that refers to vernacular architecture. Adam has documented some of Plečnik’s buildings too and shown how they reference vernacular traditions.

ID: There is quite a big food component to your biennale, can you tell me a bit about that?

JW: A number of designers have been looking at food as part of total systems. So one project we have in the biennale is Carolien Niebling’s ‘Sausage of the Future’, which isn’t just a one-off idea she had and then moved on from. She’s developed these plant-based sausages over a few years and has worked with different chefs and butchers. Carolien’s thesis is that the sausage is one of the first design food products, and most regions of the world have a sausage. Historically sausages were also about using up nutritious affordable and accessible food waste. In Slovenia, the sausage is practically a national emblem. They’re very attached to their sausages. And butchers are like a vernacular network, they are always producing, making, working locally. So instead of going for plant-based vegan industrially processed foods, we thought it would be interesting to use the existing network of butchers to to develop new climate-friendly recipes that are plant-based but rooted in the region? She’s been working with a chef (Igor Jagodic) at one of the leading restaurants in Lljubljana – Strelka – and a local butcher called Marko Butalič, on a Slovenian future sausage, which is based on buckwheat, mushrooms and wild garlic. It’s delicious.

ID: Can you tell talk me through the venues in town that will be used for the Biennial?

JW: It centres on MAO, the museum of architecture and design, which is slightly outside the centre in a rather extraordinary Renaissance castle. So the main exhibition is there. Then we also have a satellite programme around the city and that’s mainly in three places. One is a new rather extraordinary art centre that opened last year called Cukrarna, which is next to a derelict building called Palazzo Cukrarna. Here we will have three projects. The third site is the little Plečnik kiosk right in the centre of the city I already mentioned and the fourth is a building site occupied by a local collective called Krater who are doing a project called ‘Forbidden vernaculars’ looking at rammed earth (the word forbidden refers to the fact that there is no legislation in Slovenia to build with earth). It’s on a massive site in the heart of the city where there’s going to be a new Justice building at some point but that has been abandoned for some years. They’ve been working there for a couple of years developing materials from the site. They’ve made a paper out of Japanese knotweed, an invasive species there as here, they’ve experimented with mycelium and also rammed earth construction. In June there will be a workshop with designers and architects with Atelier LUMA and BC architects fromBelgium. On the opening weekend, Slovenian collective Robida will be sowing the buckwheat on the building site too.

ID: Can you talk briefly about the exhibition design?

JW: We wanted to reduce the impact of the exhibition design as much as possible because temporary exhibition designs are notoriously wasteful. But sometimes it’s hard to just rejig a little bit and you have to take a very different approach to be as far reaching as possible. So we interviewed various architects with our brief and selected Slovenian architects Medprostor who came up with the idea that we would build the entire exhibition from firewood. After we have used it, it will be collected and sold on as usual. It’s deliberately quite a provocative move as the whole thing will be this extraordinary landscape of plinths of firewood held together by shipping straps and metal bands (that can also be reused) embodying and expressing our theme. Firewood in Slovenia is still commonly used to heat homes and is very much a byproduct of the forestry industry, which is a big industry, so we are looking at something that’s absolutely an everyday vernacular. Bringing it into a museum course has been pretty challenging and getting hold of the right quantities of dry firewood at the right lengths in the summer too. It makes a strong statement and is deliberately quite strange. We want to make people stop and think.

BIO27 Super Vernaculars – Design for a Regenerative Future runs from May 26 to September 29, 2022.

read more

DesignWire

13 Highlights from the 2022 La Biennale di Venezia

The 2022 La Biennale di Venezia opened its doors last week. The 59th International Art Exhibition runs through November 27 in Venice.

DesignWire

Masa Galeria’s First New York Exhibition Offers a Closer Look at Mexican Modernism

Check out highlights from the Mexican design gallery Masa Galeria’s first New York exhibition, Intervención/Intersección.

DesignWire

Salone del Mobile to Spotlight Sustainable Design

Milan is getting serious about global warming. The 60th edition of Salone del Mobile, the world’s largest furniture fair, which this year runs from June 7 to 12, has taken on climate change, placing a strong focus on s…

recent stories

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Jonah Markowitz, Production Designer For HBO’s New Crime Thriller

Ride along with Jonah Markowitz to see how this production designer effortlessly builds immersive worlds for projects like HBO’s Duster.

DesignWire

Pierce Brosnan’s Enduring Passion Takes Shape In New Porcelain Series

See how James Bond actor Pierce Brosnan teams up with designer Stefanie Hering to produce a handcrafted collection of vases with proceeds going to charity.

DesignWire

Interior Design Hall of Fame Members: View by Year

From the past to the present, meet the celebrated names and trailblazers who have all been inducted into the Interior Design Hall of Fame.