Sou Fujimoto Architects Draws on the Local Landscape for House of Music, Hungary

Beethoven would be pleased. The famously outdoorsy composer of the Pastoral Symphony translated nature into sound, so—were he in Budapest today, encountering the House of Music, Hungary—he would understand its translation into architecture. Just completed, the three-story, 97,000-square-foot cultural facility stands amid woodlands in the capital’s 200-hundred-year-old, 300-acre City Park. Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto has designed the building like a forest canopy, with more than 30,000 abstract metallic leaves decorating the ceiling of a shallow, organically shaped dome hovering above a 320-seat glass-enclosed concert hall, a smaller auditorium, and an open-air stage. The striking design bested 170 entries in a competition.

The roof, its underside an airy filigree of gold foliage on a black background, matches the height of the arboreal canopy of the surrounding park, establishing a continuum from real nature outside to built nature inside. “My interest in architecture is how to integrate natural things and architecture,” Fujimoto notes, “not to mix them, but to translate architecture into nature and nature into architecture.” For centuries, composers have responded to the acoustic properties of concert halls, cathedrals, and other performance spaces. Fujimoto adds nature to the equation: The architecture of music and the music of architecture triangulate off his interpretation of trees in a wood.

What makes this metaphor of built nature possible is glass, which distinguishes the House of Music from the type of building that has long hosted Beethoven symphonies. Fujimoto eliminated the opaque walls that have always introverted symphony halls, dematerializing the entire perimeter of the structure with floor-to-ceiling glazing—94 custom panels in all, some almost 39 feet tall. Flat glass provides an acoustically unfriendly surface, but Japanese firm Nagata Acoustics, veterans of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles and the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg, Germany, have ensured warm, blended sound by zigzagging the panels. Performers and audiences make and hear music while seeing the enveloping park, the architecture establishing a synesthetic continuum between notes and nature.

“We were enchanted by the multitude of trees in the City Park and inspired by the space created by them,” says Fujimoto, who is best known in the West for 2013’s miragelike Serpentine pavilion in London and a 2019 apartment building in Montpellier, France, a treelike structure bristling with white, cantilevered terraces and awnings. “I envisaged the open floor plan, where boundaries between inside and outside blur, as a continuation of the park.”

Given the transparency of the ground floor, park visitors can see through the building to the other side. Even inside, they experience the effect of light filtering through a forest canopy and dappling the ground, thanks to nearly 100 apertures that puncture the roof to serve as light wells. Sound waves inspired the undulating roof, which changes in depth, though always remaining lower than the tree line.

The simplicity of a canopy floating over an open interior landscape, however, is only apparent. Comprising three levels, the structure is both an iceberg and a tree house: A permanent exhibition on the history of music, galleries for temporary shows, and a hemispherical dome for audio projections occupy the basement; the ground floor houses the performance venues; and, above the leafy ceiling, attic space in the roof accommodates a library, classrooms, archives of Hungarian pop music, and offices. An irresistible, dramatically sculpted spiral staircase connects all floors. In fine weather, performers on the open-air stage play to an audience on bleachers embedded in the adjoining landscape.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s famous glass-and-black-steel National Gallery in Berlin established the precedent for a roof hovering over a vast open space with a basement for public functions. Here Mies’s square canopy has been replaced by an organically shaped, decorated form shot through with light. The paradigm has shifted: Nature has replaced the machine, and decoration, the idea of structure. There’s a social shift, too: Transparency allows the public visual access to the inner sanctum, erasing the elitist overtones of a building intended for ticketholders only. Glass helps actualize the goal of a facility invitingly named a “house,” which is to appeal to a wide spectrum of musical tastes, from pop and folk to jazz and classical. The permanent exhibition downstairs uses interactive technology to tell the story of two millennia of European music. The program is educational and embracing rather than exclusionary, its architecture a teaching instrument. Invoking nature through design ingratiates the institution to a broad audience.

The building is the first of several planned for Liget Budapest, a controversial project by the government of Viktor Orban, Hungary’s far-right prime minister, to transform the historic park into a museum district. For all the House of Music’s formal originality, the architect and his team’s design process was conventional: They researched the site, the project’s cultural background, and the whole brief, and then sketched and chatted, eventually arriving at the key concept. “Understanding the fundamental relationship between people and people, and people and nature is the core of architecture,” Fujimoto says, concluding on a musical metaphor: “Sticking to the budget, sticking to the surroundings, reacting to the requirements—everything is harmonized.”

read more

Projects

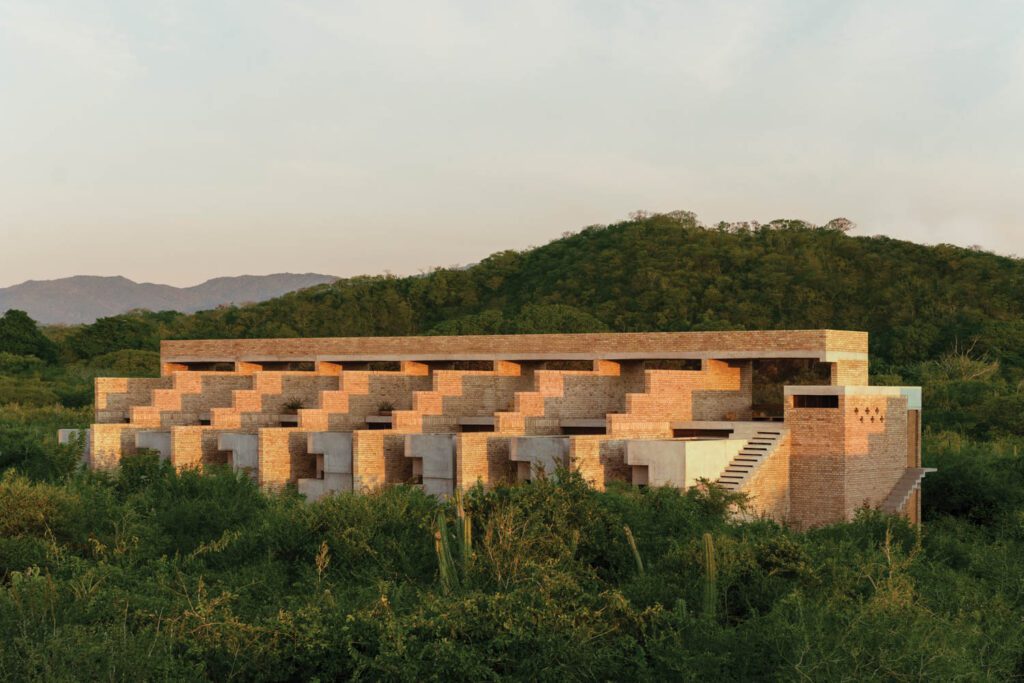

This Oaxacan Wellness Retreat Designed by Taller de Arquitectura X Preserves the Local Landscape

Hotel Terrestre not only restores visitors but also has a minimal carbon footprint. The Oaxacan wellness retreat is entirely solar-powered and made from and by local materials and artisans—a trend in vacation propertie…

Projects

Richardson Pribuss Architects Designs an Artists’ Residence in Mill Valley, California

When a New York–based artist couple decided they needed an exurban getaway, they opted out of the usual suspects. No Hamptons, Hudson Valley, or Berkshires. Instead, they cast their net some 3,000 miles away and landed…

Projects

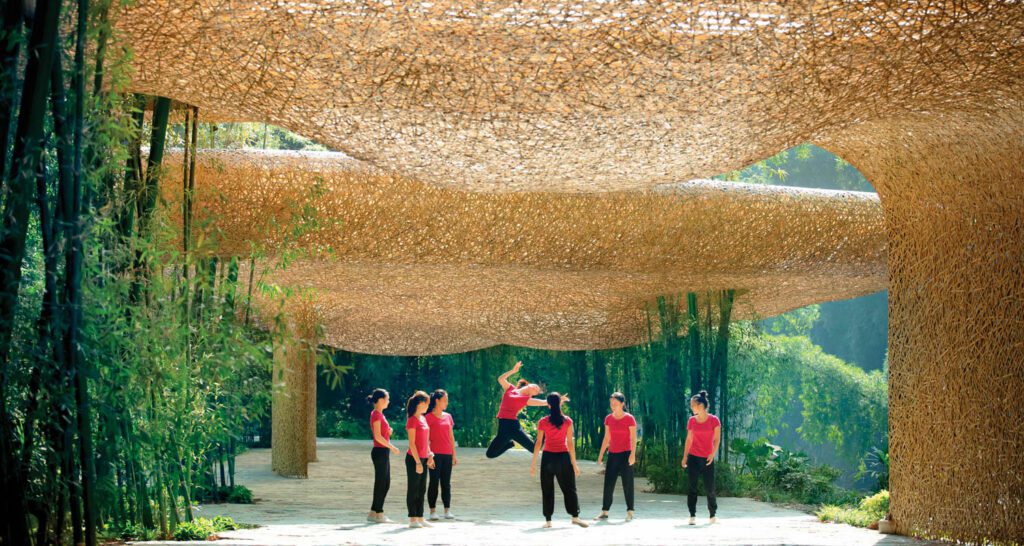

LLLab’s Locally Sourced Bamboo Pavilions in China Take Home a Best of Year Award

Chief designer Hanxiao Liu and his team at LLLab. were commissioned to provide shelter for audiences waiting between the entry pagoda and the stage, which lie at opposite ends of the island, for the 600-person musical Im…

recent stories

Projects

Raise A Toast To This Sleek Spirits Shop In Portugal

Tiago do Vale’s refreshing design for Bottles Congress showcases the shop’s wine with a smooth material palette of pine, Portuguese marble and MDF.

Projects

Sound And Design Intersect In A New Facility For Dartmouth

T+E+A+M and Stock-a-Studio’s facility for Dartmouth’s graduate sonic practice program gleams with an industrial vibe and swathes of polycarbonate panels.

Projects

A Bauhaus-Inspired Creative Space in L.A. Fosters Connection

Explore how The Lighthouse by Warkentin Associates blends Bauhaus architecture with ’90s aesthetics for a creative campus in Venice, California.